Neolithic European Farmers: Glimpses into Their Genetic World

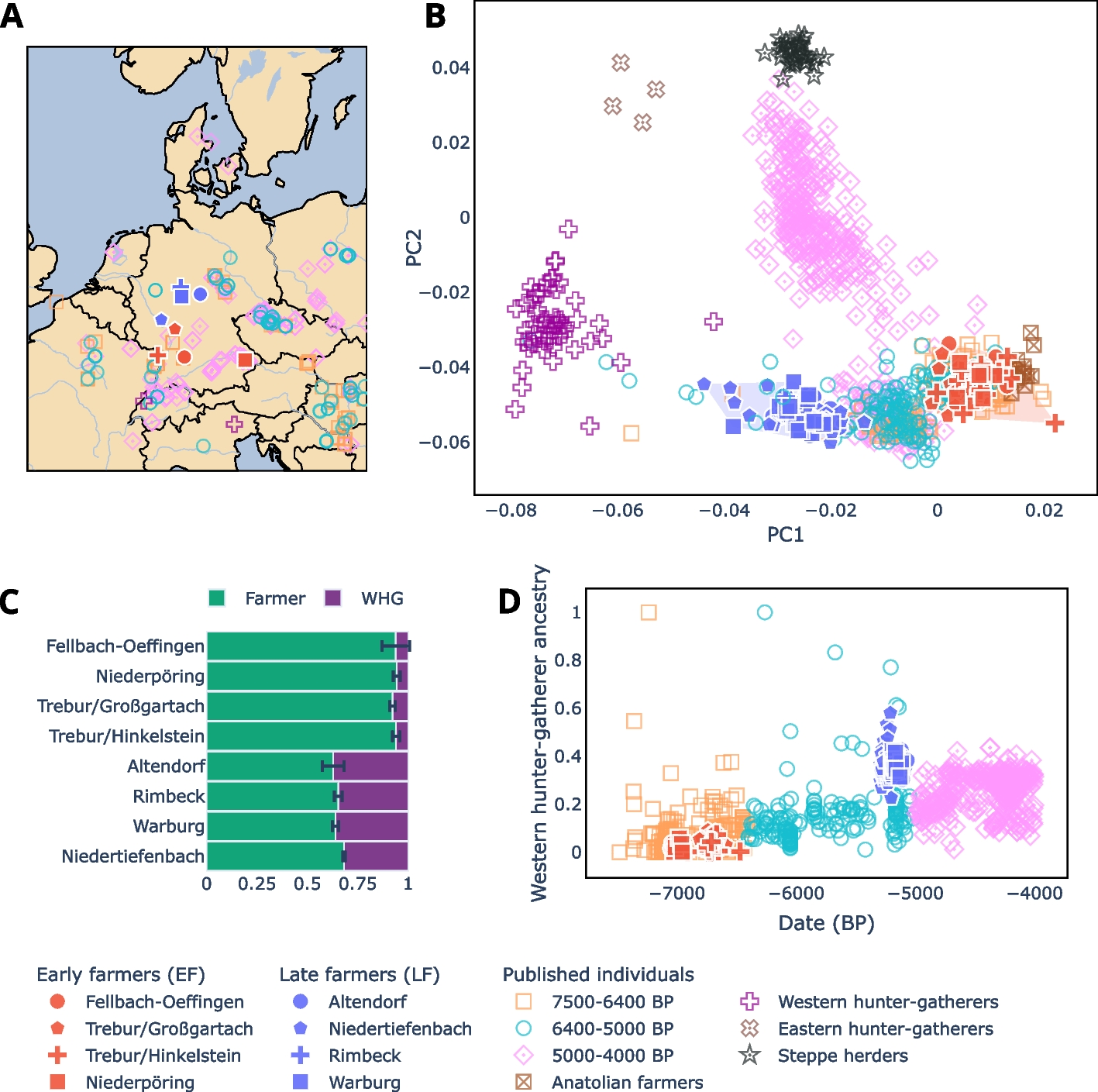

Archaeologists have unearthed invaluable insights from six sites across Germany: Niederpöring, Fellbach-Öffingen, Trebur, Altendorf, Warburg, and Rimbeck. These sites offer a panoramic view of the Neolithic transition in Europe, capturing the essence of early life and its adaptations through the ages. Discoveries from these archaeological sites spread across modern Germany offer riveting glimpses into genetic intermingling, with remains dating from the Early to the Late Neolithic telling of a world where grave offerings changed as societies evolved and intermingled.

At these archaeological sites, researchers have gathered remarkable details on the lives of ancient Europeans through the examination of 175 individuals. The Niederpöring site notably revealed traces of ancient viruses like hepatitis B and parvovirus B19 (slapped cheek fever), shining light on the microbial world surrounding these communities and painting a quiet picture of life's fragility, yet speaking to the resilience engendered by diverse genetic adaptations.

In Trebur, the burial setups of the Hinkelstein and Großgartach groups enrich our understanding of the Middle Neolithic customs, while Altendorf, Warburg, and Rimbeck take us deeper into the Wartberg culture of Late Neolithic Europe, showcasing the nuanced changes these groups experienced. The Late Neolithic Wartberg culture, particularly the community encased within the Niedertiefenbach grave, serves as a profound example of genetic diversity and cultural evolution.

Each site, from the grand megalithic formations at Niedertiefenbach to the serene gallery graves of Altendorf, acts as a window through which we observe ancient human life. They whisper tales of ancestors, exchanges made beneath vast European skies, each piece of pottery or tool a singular testament to human resilience and adaptability. The specific grave goods, pottery fragments, and burial arrangements speak volumes about the spiritual lives of these communities, echoing life's rich tapestry as threads of ancestry wove webs under the European skies.

The data indicates a significant admixture between the early Anatolian-derived farmers and the indigenous hunter-gatherer populations. These genetic exchanges, reflected vibrantly in their human leukocyte antigen (HLA) profiles - basically the ability for the immune system to fight off viruses and bacteria, elucidate the adaptive co-evolution of humans and pathogens. The genetic data from these settlements unveiled striking genetic components, with late farmers harboring a significant influx of hunter-gatherer ancestry, indicative of extensive cultural integration.

Notable shifts in genetic composition are observed as we track the transformation from early farmers (EF) to the late farmers (LF) who lingered into new eras. The EF, akin to the Linear Pottery societies, clung largely to their Anatolian roots. However, as societal lines blurred, the LF exhibited a remarkable integration of hunter-gatherer ancestry, with some communities showing 34-58% hunter-gatherer lineage component, hinting at richer cultural exchanges that shaped diverse societies thereafter.

While the variety of immune system genes (HLA) in Neolithic communities was relatively narrow compared to contemporary populations, they reveal fascinating adaptations to their environment and lifestyles. The study of HLA alleles from these remarkable sites allows us to peek into ancient immune responses, significantly varied from today's diversity. Armed with samples from 83 individuals, researchers noted significant shifts in HLA allele frequencies—a time capsule reflecting the genetic intermingling between Anatolia's agrarian pioneers and the rugged hunter-gatherers.

The alleles captured in the genomes of these farmers tell of adaptive responses to specific pathogens—a testament to the relentless march of evolution, adjusting and surviving in the vibrant context of Neolithic existence. These genetic adaptations were perhaps a communal shield against infections in relatively pathogen-free environments, highlighting the primal urgency in the ancient battle against disease.

One intriguing aspect of this demographic transformation is the occurrence of sex-biased admixture that predominantly skewed towards male hunter-gatherers in the formation of Late Neolithic farming communities. The change in Y-chromosome diversity from Early to Late Neolithic populations suggests a male-dominated influx from the hunter-gatherer groups, with sites like Altendorf showing the predominance of one Y-chromosome lineage, whereas earlier populations displayed wider variety.

This male-biased admixture from western hunter-gatherers adds depth to the narrative of Neolithic European demographic shifts. The integration of hunter-gatherer males into farming communities may have been facilitated by social structures that were accommodating new roles and identities, paving the way for regional diversity replete with new genetic resources and knowledge.

Through sophisticated kinship analyses, the relationships unearthed from places like Altendorf and Trebur tell stories of community dynamics and social cohesion. These findings highlight both close-kin networks and wider social connections, suggesting rich, intertwined communal lives interspersed with dynamic intergroup exchanges. In the Trebur, Altendorf, and Warburg sites, kinship analyses revealed familial connections across the ages, symbolizing the social tapestry of time and binding their culture's past to our present understanding.

The exploration of the Late Farmers points to transformative changes that were as much genetic as they were social. The sites of Altendorf, Warburg, and Rimbeck stood as testament to the Late Neolithic vigour, where the higher incidence of hunter-gatherer ancestry marked an era of robust genetic exchange driven by new cultural practices, romance, trade, and migration.

Such insights not only enrich our understanding of how ancestry interwoven with culture shapes identities but also underscore the vibrant legacy of these ancient communities in the genetic tapestry of today's Europeans. As you wander through the landscape of Neolithic Germany in your mind, it becomes a theatre of social convergence where graves and settlements whisper tales of cultural and genetic amalgamation, reshaping the lives of ancient people in ways that continue to reverberate through our genes today.

The exploration of ancient populations through DNA analysis provides novel insights into the interactions that shaped early European communities, particularly focusing on how genetic melding influenced immune function. The disparities found in ancient genetic data highlight intriguing questions about how specific alleles offered protection and reveal the enduring partnership between humans and their environment.

Comments