West African DNA Discovered in Seventh-Century England

West African Ancestry in Seventh-Century England

This comprehensive document explores groundbreaking archaeological and genetic findings from Kent and Dorset that reveal the presence of individuals with recent sub-Saharan African ancestry in early medieval England. These remarkable discoveries highlight the interconnected nature of ancient societies and demonstrate that cultural exchange and migration patterns were far more complex and extensive than previously understood, challenging traditional narratives about medieval Britain's demographic composition.

For centuries, history has been told through artifacts and chronicles. Now, DNA gives us a different kind of evidence — one that speaks from within. Learn how your genetic story connects to the ancient world at MyTrueAncestry.com.

The Updown cemetery, located near Eastry in Kent, represents one of the most significant archaeological discoveries of recent decades. Excavated extensively during the 1970s and 1980s under the guidance of archaeologists Sonia Hawkes and Brian Philp, this site revealed 78 inhumation burials dating primarily to the seventh century. The cemetery provides invaluable insights into early medieval burial practices and cultural exchanges that characterized this transformative period in English history.

Among the numerous burials, one discovery stands out as particularly extraordinary: a young female, estimated to be between 11 and 13 years old at the time of her death, whose DNA analysis reveals compelling genetic ties to sub-Saharan Africa. Her burial was accompanied by an impressive array of grave goods that speak to both her integration into Anglo-Saxon society and the broader networks of cultural exchange that defined the era.

The grave goods recovered from her burial include a carefully crafted knife, a bronze spoon, a intricately carved bone comb, and a uniquely decorated ceramic pot. Each of these artifacts tells a story of cultural synthesis and long-distance connections. The pot, in particular, demonstrates remarkable craftsmanship with its Frankish-influenced style and incised decorations that suggest either local production inspired by continental techniques or direct importation from Frankish territories. The bone comb, likely used for both practical grooming and decorative purposes, reflects the sophisticated material culture of the period.

Additional finds throughout the cemetery include dress accessories, weaponry, and a particularly notable Byzantine buckle, though imperfectly preserved, which hints at the extensive trade networks that connected Kent to distant corners of the known world. These artifacts collectively paint a picture of a community deeply embedded in international exchange networks, serving as a gateway between continental Europe and the Anglo-Saxon kingdoms.

The Worth Matravers site, excavated in 2011 and locally known as the 'Football Field' cemetery, provides complementary evidence for the presence of individuals with West African ancestry in seventh-century England. This smaller cemetery contained 21 graves and offers crucial insights into early medieval burial practices in coastal Dorset, a region that played an important role in maritime trade and cultural exchange.

The most significant discovery at this site is an adult male, aged between 17 and 25 years at death, whose genetic profile shares remarkable similarities with the young female from Updown. His burial was relatively modest, accompanied by a copper-alloy belt buckle that nevertheless demonstrates connections to broader trade networks spanning the English Channel and beyond.

Initially thought to contain Roman-period burials, radiocarbon dating conclusively established the cemetery's seventh-century date, placing it within the same chronological framework as Updown. The site's location, inland from the English Channel coast, reveals how Mediterranean and Atlantic trade currents influenced even seemingly remote communities, creating nodes of cultural exchange throughout early medieval Britain.

The burial orientations and relatively sparse grave goods at Worth Matravers suggest different cultural practices compared to the richer burials at Updown, yet both sites demonstrate the integration of individuals with diverse ancestral backgrounds into local community structures. The presence of what may be a stone anchor among the grave goods further emphasizes the maritime connections that characterized this coastal region.

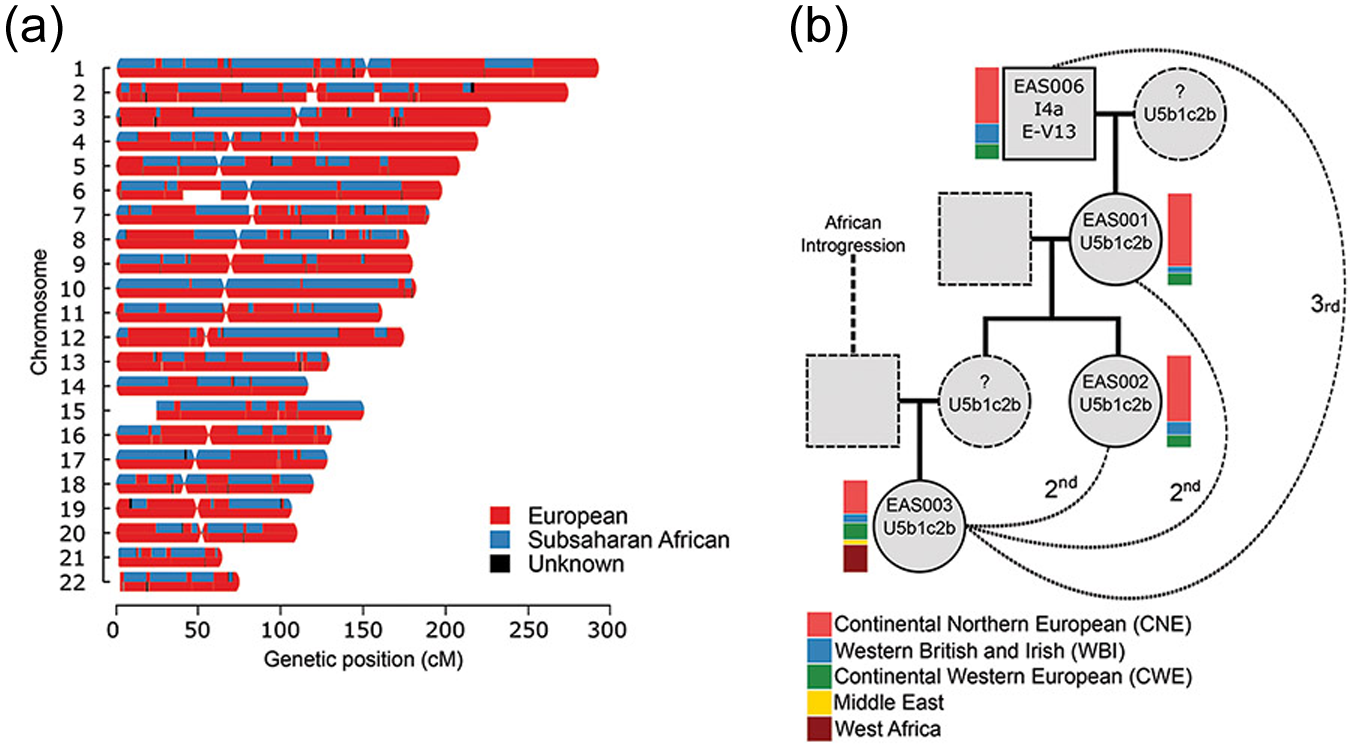

The application of advanced ancient DNA analysis techniques has revolutionized our understanding of population movements and genetic diversity in early medieval England. The genetic material extracted from both the Updown female and the Worth Matravers male reveals a complex story of ancestry that spans continents and challenges conventional assumptions about medieval demographics.

Both individuals exhibit mitochondrial and genomic markers consistent with a mixed European and sub-Saharan African heritage, with approximately 20-40% of their ancestry traceable to West African populations, particularly groups similar to the modern Yoruba people. This genetic signature indicates not ancient admixture but rather recent ancestral contact with West Africa, suggesting that either these individuals themselves or their immediate ancestors were part of migration pathways active during the sixth and seventh centuries.

The genetic analysis also reveals fascinating details about family relationships within these communities. Evidence suggests familial connections between some individuals at Updown, including what appear to be grandmother-granddaughter and aunt-niece relationships, indicating that people of mixed African-European heritage were not isolated individuals but part of established family networks within Anglo-Saxon society.

These findings align with the broader historical context of the Byzantine reconquest of North Africa between 533-534 AD, a period marked by significant population movements and cultural exchanges across the Mediterranean world. The genetic evidence suggests that the trans-Saharan trade networks and Mediterranean maritime routes facilitated not just the movement of goods but also the migration of people across vast distances.

The presence of individuals with West African ancestry in seventh-century England must be understood within the broader context of early medieval migration patterns and cultural exchanges. This period witnessed unprecedented levels of interaction between diverse populations across Europe, Africa, and the Mediterranean, facilitated by expanding trade networks and political upheavals that displaced populations across vast distances.

The Byzantine reconquest of North Africa created new pathways for cultural and demographic exchange, connecting the Mediterranean world in ways that facilitated the movement of people, goods, and ideas. Archaeological evidence from both Updown and Worth Matravers suggests that these individuals were fully integrated into their local communities, buried according to contemporary customs and accompanied by grave goods that reflect both local traditions and international connections.

Kent's position as a gateway to continental Europe made it a natural hub for cultural exchange, but the presence of similar individuals in Dorset demonstrates that these connections extended throughout southern England. The integration of people with diverse ancestral backgrounds into Anglo-Saxon communities speaks to a level of cosmopolitanism that challenges traditional narratives about medieval insularity and ethnic homogeneity.

The grave goods associated with these individuals particularly the decorated pottery, imported combs, and metal work reveal sophisticated networks of production and exchange that connected local communities to continental workshops and Mediterranean trade circuits. These artifacts serve as material evidence of the cultural synthesis that characterized early medieval England, where local traditions merged with influences from across the known world.

These extraordinary discoveries fundamentally reshape our understanding of early medieval English society, revealing levels of diversity and international connectivity that were previously unrecognized. The integration of individuals with sub-Saharan African ancestry into Anglo-Saxon communities demonstrates that medieval England was far more cosmopolitan than traditional historical narratives have suggested.

The careful burial of these individuals according to contemporary customs, complete with appropriate grave goods, indicates their full acceptance within their communities. This challenges assumptions about medieval attitudes toward ethnic and cultural difference, suggesting instead societies capable of incorporating and celebrating diversity within established social frameworks.

The archaeological evidence also highlights the importance of trade networks and migration patterns in shaping early medieval demographics. The connections revealed between England, continental Europe, the Mediterranean, and ultimately West Africa demonstrate the global nature of cultural exchange long before the advent of modern globalization.

Discover how your DNA connects to ancient civilizations at www.mytrueancestry.com.

Comments