The Mursa Mass Grave: Roman Military History in Croatia

The Mursa Mass Grave: A Window into Roman Military History

The ancient Roman city of Mursa, now known as Osijek in modern-day Croatia, has revealed one of the most compelling archaeological discoveries of recent decades. In 2011, during excavations for a future university library, archaeologists uncovered a mass grave within a disused water-well containing seven remarkably preserved adult male skeletons dating to the turbulent mid-3rd century CE. This extraordinary find provides unprecedented insights into the lives and deaths of Roman soldiers during one of the empire's most chaotic periods.

Behind every ancient burial site or artifact lies a human story - one that might, unexpectedly, connect to yours. Discovering that connection can be as simple as uploading your DNA at www.mytrueancestry.com.

Mursa held a strategically crucial position along the imperial border (limes) by the Danube River, serving as both a military stronghold and commercial hub. The city's importance was recognized by Emperor Hadrian, who elevated its status to a colony in 133 CE. During the 'Crisis of the Third Century' (235–284 CE), this frontier settlement became a focal point of violence and political upheaval that characterized this tumultuous era.

The mass grave's discovery coincides perfectly with historical accounts of the Battle of Mursa in 260 CE, where Emperor Gallienus confronted the rebellious usurper Ingenuus. Radiocarbon dating of the human remains aligns precisely with this violent confrontation, suggesting these seven men were casualties of this significant military engagement. The grave's location adjacent to the city walls points to a rapid burial following a catastrophic event, with the stacked arrangement of skeletons indicating they were interred in quick succession after their deaths.

Bioarchaeological analysis reveals these individuals possessed the physical characteristics consistent with Roman legionaries. All seven men were in their prime, aged between 18 and 50 years, with robust stature and an average height of 172.5 cm—measurements that align with Vegetius's documented criteria for Roman military recruitment. Their skeletal remains display significant musculoskeletal markers indicative of a life dedicated to military service, including evidence of rigorous physical training and combat experience.

The pathological findings paint a vivid picture of the harsh realities faced by these soldiers. Multiple skeletons exhibit healed blunt force trauma alongside fresh perimortem injuries consistent with weapon strikes from spears, swords, and arrows. One particularly striking injury includes a puncture wound on the manubrium, exemplifying the deadly nature of their final confrontation. Beyond battle scars, the remains show evidence of respiratory infections through periosteal reactions on the ribs, likely common in the cramped quarters of military life.

Stable isotope analysis provides fascinating insights into the daily lives of these soldiers through their dietary habits. The carbon and nitrogen isotope data reveals a predominantly plant-based diet centered on C3 plants such as wheat and barley, with limited animal protein intake. This nutritional profile perfectly matches historical accounts of Roman military rations, which primarily consisted of wheat supplemented occasionally with meat, legumes, and other provisions when available.

The uniformity of their dietary signatures suggests these men shared common provisioning, further supporting their identification as members of the same military unit. This wheat-centric diet was the backbone of Roman military logistics, enabling the empire to maintain large standing armies across vast territories through standardized supply chains.

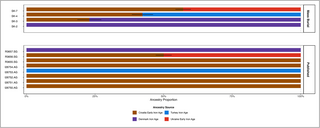

Perhaps the most remarkable revelation comes from ancient DNA analysis, which unveils a striking genetic diversity among these soldiers. Unlike the genetic continuity observed in local Early Iron Age populations, these seven men possessed heterogeneous ancestries spanning Northern, Central, and Eastern Europe, with possible Mediterranean influences. This genetic mosaic reflects the cosmopolitan nature of Roman military recruitment, which drew soldiers from across and beyond the empire's vast expanse.

The genomic data illustrates how the Roman army served as a melting pot of ethnicities and cultures, bringing together individuals from disparate backgrounds under the banner of imperial service. This diversity was both a strength and a necessity for Rome, as the empire's military needs far exceeded what local recruitment could provide. The presence of varied ancestries among the Mursa soldiers exemplifies the complex demographic dynamics that characterized Roman frontier forces.

The excavation yielded additional contextual evidence supporting the military interpretation of these remains. Small finds including Roman coins dated to the appropriate period help anchor the chronological framework, while the grave's construction within a repurposed water-well suggests emergency burial circumstances. The absence of elaborate grave goods indicates these were likely common soldiers rather than officers, consistent with their rapid interment following battle.

The site's stratigraphy and the positioning of the remains provide crucial information about the sequence of events. The layered arrangement of skeletons suggests they were buried systematically but hastily, possibly by surviving comrades or local inhabitants in the aftermath of the conflict. This type of mass burial was not uncommon during periods of intensive warfare, when individual funeral rites were impractical due to the scale of casualties.

The Mursa mass grave serves as a powerful microcosm of the broader Crisis of the Third Century, a period marked by political instability, economic decline, and constant military conflict. During this era, the Roman Empire faced unprecedented challenges including barbarian invasions, civil wars, plague, and economic collapse. The rapid succession of emperors, many of whom met violent ends, created an atmosphere of perpetual uncertainty and conflict.

The battle that claimed these seven soldiers was part of this larger pattern of internal strife. Emperor Gallienus's confrontation with Ingenuus represents just one of many conflicts between legitimate rulers and usurpers who sought to claim imperial power. The harsh measures employed by Gallienus against dissenters, documented in historical sources, provide context for the violent fate that befell these soldiers.

This investigation exemplifies the power of modern multidisciplinary archaeological approaches. The integration of traditional osteological analysis with cutting-edge techniques including ancient DNA extraction, stable isotope analysis, and radiocarbon dating has created an unprecedented level of detail about these ancient lives. Each analytical method contributes unique insights that, when combined, construct a comprehensive narrative far richer than any single approach could achieve.

The bioarchaeological methodology employed here serves as a model for investigating mass graves and conflict archaeology more broadly. By combining skeletal analysis with genetic and chemical data, researchers can address questions about identity, mobility, diet, and social organization that would be impossible to answer through traditional archaeological methods alone.

The findings from Mursa contribute significantly to our understanding of Roman military organization and recruitment practices during the imperial period. The genetic diversity observed among these soldiers demonstrates the truly international character of Roman forces, challenging earlier assumptions about military demographics. The evidence suggests that by the 3rd century CE, Roman military units were ethnically diverse organizations that brought together individuals from across the known world.

The standardized diet and physical conditioning evident in these remains also illuminate the effectiveness of Roman military logistics and training systems. Despite their diverse origins, these soldiers shared common experiences of military life that shaped their bodies and health in similar ways. This standardization was crucial to Roman military success, creating cohesive fighting units from disparate populations.

Discover how your DNA connects to ancient civilizations at www.mytrueancestry.com.

Comments