Neolithic Cannibalism in Prehistoric Iberia: El Mirador Cave

Neolithic Cannibalism at El Mirador Cave

In the heart of the Sierra de Atapuerca, El Mirador Cave has offered archaeologists a window into the mysterious practices of Neolithic people. Among the finds, human remains have painted a vivid picture of past behaviors hinting at cannibalism, a topic both fascinating and haunting. The remains tell a story not just of survival but also of complex social interactions and rituals that challenge our understanding of prehistoric European communities.

The spectacular karst system of the Sierra de Atapuerca, with El Mirador Cave nestled within, has been a rich source of archaeological discovery since the late 1990s. Excavations have revealed layers that range from the Neolithic to the Middle Bronze Age, each telling its own tale of human life. In total, over 5,000 human remains have been unearthed, scattered throughout different sectors of the cave including the central Test Pit, Sector 100, and Sector 200. These remains offer clues about the practices of those who once called these chambers home, creating a comprehensive picture of prehistoric life in the region.

The archaeological work at El Mirador began in 1999 and has continued to expand our understanding of prehistoric life and death practices. The site's exceptional preservation conditions have allowed researchers to uncover a treasure trove of human remains, offering a peek into a past where the line between ritualistic practices and survival was often blurred. The dig sites have yielded evidence spanning millennia, providing insights into the cultural transitions from foraging to settled farming communities.

Genetic data from archaeological remains has transformed our understanding of migration, identity, and belonging. Seeing where your DNA overlaps with those findings can offer a new, personal lens on human history — explore it at www.mytrueancestry.com.

The archaeological record shows a fascinating blend of burial practices that evolved significantly over time. In some instances, human bones were mixed with animal remains and artifacts, such as ceramics and stone tools, suggesting a rich cultural context. Unlike simple burials, these finds paint a picture of rituals that go beyond mere necessity. In what appears to be a ceremonial act, some skulls were transformed into skull cups, possibly used in rituals that mingled the living with the memory of the dead. Imagine the drinking cups of today, but made from the very cranium of an ancestor or enemy.

As the Neolithic gave way to the Bronze Age, the Iberian Peninsula witnessed evolving funerary rites. Early on, simple burials were the norm, but later, we observe a stunning variety of practices. These ranged from secondary burials, where human remains mingled with animal bones and artifacts, to grand collective interments within megalithic structures. Curiously, by the Bronze Age, a shift towards individual burials began. Some graves boasted grave goods, while others lacked such offerings, signaling varying social statuses or beliefs.

Radiocarbon dating and strontium isotope analysis tell us that the individuals who were subject to cannibalism were locals, embedded in the community that lived and died in this cave. Examining these remains reveals a cross-section of society including young children as young as seven, adolescents, and older adults. Evidence of cannibalism indicates a systematic approach with marks of butchery remaining on bones, signs of boiling, and even tooth marks hinting at consumption. Could this be a macabre reflection of survival, perhaps a ritual to internalize the deceased, or simply a violent episode in the cave's history?

The use of strontium isotope analysis has been particularly revealing. By examining the 87Strontium/86Strontium ratios in femoral remains, scientists can determine geographical origins. The methodology employed involved meticulously extracting strontium from the bones, followed by careful measurement using state-of-the-art mass spectrometry techniques. The data from five individuals in El Mirador suggest a local origin, adding a geographical layer to the understanding of who these people were and challenging earlier assumptions about the motivations behind these practices.

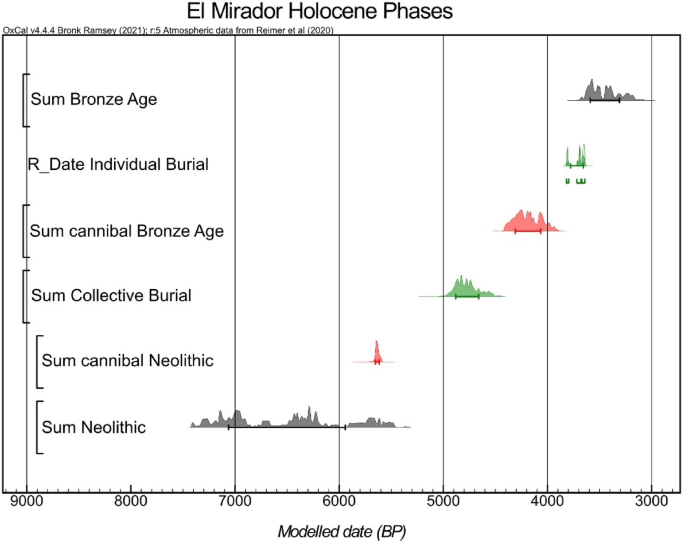

Archaeologists applied taphonomic analysis—the study of decay and fossilization—to trace the mysterious manipulations of these ancient bodies. Cut marks, tooth imprints, and even the utilization of skulls as ceremonial cups suggest a complex cultural tapestry where death often wore a multi-faceted guise. Bayesian statistical analysis shed light on a specific cannibalistic event dating between 5,709 to 5,573 years ago, roughly marking the end of the Neolithic occupation at the site.

The analysis suggested this incident of cannibalism was separate from later Bronze Age episodes and highlighted the unusual nature of the practice within these communities, as there was no sign of famine driving it. This suggested a more complex cultural or ritualistic rationale behind the consumption of human flesh, forcing researchers to explore interpretations beyond simple explanations of hunger.

While famine and funerary rituals are plausible explanations for these acts, the uniformity of how remains were treated suggests a different narrative. The end of the Neolithic era in El Mirador coincides with this episode, pointing perhaps to social strife or conflict-driven motives. One theory suggests that these remains are the aftermath of intergroup violence, a grim testament to turbulent times. This echoes other instances across Europe, where Neolithic communities were not strangers to warfare cannibalism—a practice infused with both ritual significance and territorial desperation.

The revelation that the cannibalised individuals were of local origin challenges earlier assumptions about the motivations behind these practices. It was once thought that such extreme actions might be driven by encounters with strangers or outsiders. Instead, it points to a more intimate connection among the local populations and suggests complex social dynamics within these prehistoric communities.

Caves like El Mirador were not mere shelters but held significant communal and cultural roles. Here, bones mingled with faunal remains and everyday items, crafting a narrative that defies simple explanations of grief or commemoration. These interments reflect a deeper, possibly ritualistic engagement with death that speaks to the sophisticated social structures of these ancient peoples.

The extraordinary preservation and range of these findings help deepen understanding of the interplay between cultural practices and mortality in prehistoric Europe. At El Mirador, different phases of occupation have been uncovered, revealing human remains across four archaeological contexts. Notably, a layer known as Level MIR4 revealed skull cups, suggesting ceremonial use, and numerous bones exhibiting signs of cutting and heating, further indicating processing of bodies—whether for ritual or sustenance remains a subject of debate.

Discover how your DNA connects to ancient civilizations at www.mytrueancestry.com.

Comments