Deciphering the Genetic Ancestry of the Sarmatian Peoples

The Sarmatian Period in the Carpathian Basin

The Sarmatians were a nomadic people believed to have migrated from the Central Steppe region and the Southern Urals, arriving in the Carpathian Basin during the 1st century CE, with some evidence suggesting earlier presence during the 4th to 2nd centuries BC. Their historic footprint is widespread across Hungary and parts of modern Romania, leaving behind numerous archaeological sites including cemeteries rich with artifacts. Prominent among these discoveries is the Apátfalva cemetery in Hungary, where the ditches and burial orientations tell unique stories of Sarmatian customs and their adaptation to settled life.

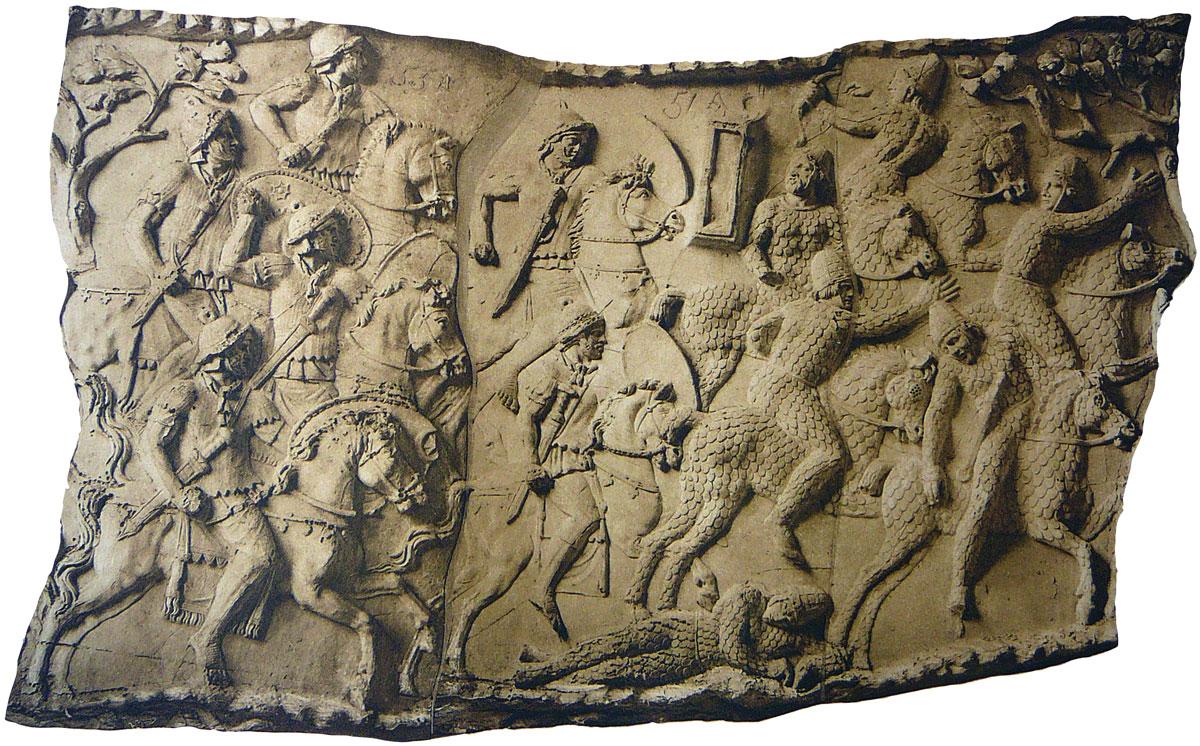

Grave goods such as jewelry, military accoutrements, and elaborate gold ornaments were frequently discovered, highlighting connections with other contemporary cultures including the Romans and various Germanic tribes. The presence of these artifacts indicates not merely trade relationships but deep cultural integration that occurred over centuries of interaction. Excavations at sites like Budapest XVII. Rákoscsaba and Péceli út reveal the sophisticated nature of Sarmatian material culture and their strategic importance in regional power dynamics.

Sites such as the Csanádpalota cemetery reveal Sarmatian communities' remarkable adaptation from nomadic to settled lifestyles upon their entry into the Carpathian Basin. Despite noted looting over the centuries, the rich remnants found provide invaluable insight into burial customs and social organization. Items like spindle whorls, belt buckles, bronze earrings, and D-shaped buckles offer glimpses into daily life, social structure, and the technological sophistication of these ancient peoples.

The graves often had varying orientations, with standard directions being S-N, SE-NW, or E-W, suggesting cultural influences from various directions and the complex religious or cosmological beliefs that guided their burial practices. Particularly intriguing are discoveries at sites like Botoșani in Romania, where a cemetery with artificially deformed skulls suggests unique burial customs that link these populations to distant steppe traditions. Romania's Pogorăști cemetery presents 28 burial sites that illustrate the persistence of cranial deformation practices, connecting these communities to their ancestral heritage.

Artifacts from these sites reflect a remarkable blend of local Celtic-Dacian traditions with Sarmatian and Roman influences, creating a unique cultural synthesis. The use of Roman-style mirrors and ceramics indicates significant Roman influence during the imperial period, while weaponry and metalwork illustrate the persistent steppe heritage that defined Sarmatian identity. The presence of animal bones, particularly horse remains, in burial contexts demonstrates the continued importance of pastoralist traditions amidst increasingly settled agricultural lifestyles.

Archaeological evidence from the Nagykálló – Kis Ludas-tó site revealed extraordinary burial practices, showcasing treasures of beads, bronze artifacts, and the renowned warrior grave assemblages. Radiocarbon dating positioned these burials in the critical Sarmatian period of the 3rd–4th centuries CE, providing crucial chronological framework for understanding the cultural transitions occurring during this transformative era in Central European history.

Genetic analysis has significantly deepened our understanding of Sarmatian connections far beyond what surface archaeology alone could reveal. Radiocarbon dating, when paired with sophisticated genetic analysis, identifies important discrepancies due to dietary practices such as fish consumption impacting radiocarbon reservoir effects, particularly notable in certain individual burials from riverine environments. Such analyses confirm the mixture of genetic lineages, showcasing Sarmatians as a remarkably diverse group with ties to multiple Eurasian populations.

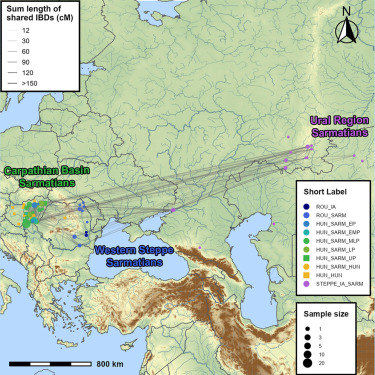

The analysis of identity-by-descent connections among ancient Sarmatian populations reveals intricate networks of kinship that transcended geographical boundaries. Groups such as STEPPE_IA_SARM exhibit unusually high densities of internal genetic connections, speaking to their mobile, semi-nomadic lifestyle and the extensive genealogical networks they maintained across the vast Eastern European plains. Individual cases like HVF-4, a Northern European genetic outlier from the period, demonstrate the most expansive genealogical networks in the dataset, linking individuals from the Sarmatian through to the Avar Period.

The Sarmatians established themselves in the Carpathian Basin following the decline of the Dacian Kingdom after 106 CE, primarily settling in the Great Hungarian Plain. They strategically took advantage of political vacuums to expand their settlements east of the Tisza River, creating networks of family cemeteries and elaborate burial sites featuring exotic goods that archaeologists term the "gold horizon" phenomenon. This expansion was accompanied by swift assimilation of local populations and the adoption of elements from Dacian and Roman provincial cultures.

Through events like the Marcomannic Wars (166-180 CE), Sarmatian forces frequently engaged with Roman territories, demonstrating their military capabilities and strategic importance. Their complex relationships with neighboring tribes like the Quadi and Vandals, combined with their central role in both raiding and trading with Roman provinces, highlighted their remarkable adaptability and political acumen. Archaeological records show that although Sarmatian tribes like the Iazyges became entrenched among settled communities, they successfully maintained essential aspects of their nomadic traditions.

As the 4th century progressed, seismic shifts occurred throughout the eastern Carpathian Basin with the arrival of the Huns from the 370s onward. Archaeological evidence reveals the infiltration of new populations and cultural influences, with burials from this era containing more weapons and exotic artifacts than in previous periods. The influence of the Marosszentanna-Chernyakhov culture from the east and the Przeworsk culture associated with the Vandals becomes particularly apparent in the archaeological record.

Despite apparent disruptions, surprising continuity emerges in settlements, particularly in southern regions around Szeged and Csongrád. Sites from the Hunnic period exhibit compelling cultural fusion, with contemporary artifacts found alongside traditional Sarmatian relics. Even after the collapse of the Hunnic Empire, historical accounts speak of Sarmatian leaders maintaining political presence in various regions until the 470s, when they eventually became integrated into the developing Gepid Kingdom.

The archaeological and genetic collaboration presents the Sarmatians as a dynamic society connected across vast geographical areas through networks of trade, warfare, diplomacy, and migration. Sites throughout the Carpathian Basin contribute important fragments to this intricate historical mosaic, piecing together the story of these remarkable people using both their material remains and genetic heritage. The synthesis of traditional archaeological methods with modern genetic analysis brings to life the rich tapestry of ancient lives and reveals the Sarmatians not merely as subjects of the distant past, but as vivid players in human history whose cultural and genetic legacies continue to inform our understanding of ancient European populations and their enduring impact on the development of medieval Central Europe.

Comments