The Epic Journey of Salmonella traced through DNA

In an exhilarating exploration of our past, the study of Salmonella enterica has uncovered fascinating details about early human societies and their encounters with this pervasive pathogen. Our journey begins over 5,000 years ago, where ancient genomes from a multitude of archaeological sites across Eurasia unravel a story of evolution and adaptation that spans millennia.

Imagine walking through the remains of ancient settlements across Eurasia, from the sunlit expanses of the Iberian Peninsula to the remote steppes of present-day Mongolia. Amidst these whispers of the past, archaeologists and geneticists have unearthed a different kind of historical treasure—a treasure not made of gold or precious stones but of ancient DNA sequences from Salmonella enterica, a pathogen that once tread the same earth as our ancestors.

The investigation spanned a vast expanse of archaeological landscapes, where bustling trade cities of yore and vibrant communities on the brink of the Bronze Age served as canvases upon which Salmonella painted its enduring legacy. Excavations ranging from Spain to Mongolia have revealed the ancient DNA of S. enterica, offering a unique glimpse into its evolutionary path. Specifically, the Nepluyevsky site in Russia, dating back to ca. 2010-1630 BCE, and the Kamenice site in Albania from ca. 770-540 BCE were host to striking prehistoric outbreaks of S. enterica.

When we read about vanished civilizations, it’s easy to forget that their descendants still walk among us. If you’re curious which of them you might share roots with, you can explore your own genetic links at www.mytrueancestry.com.

The archaeological treasures found in these regions opened a time capsule of knowledge, revealing more than just the presence of the pathogen. The analysis of 53 new ancient genomes, spanning from 3500 BCE to 1300 CE, displayed astonishing host adaptations—tales of convergent evolution etched into the very DNA of these ancient strains. These pathogens did not just adapt over time; they played a role in shaping the health and disease narratives of human societies.

Through archaeological tooth samples, researchers identified prehistoric lineages across a geographical stretch from Spain to Mongolia. Intriguingly, a sister lineage to the modern Birkenhead strain was detected as far back as 3600 BCE. This indicates that these pathogens were more geographically widespread and populated the ancient ecosystems of Europe well before they were ever documented in historical texts.

Among the ancient genomes discovered, significant figures include an Early Bronze Age individual from Bulgaria, and others from late Chalcolithic Turkey. These early ancestors, though long silent, have through their remains, lent a voice to the pathogens that once inhabited them. At Nepluyevsky, findings suggested a prehistoric Salmonella outbreak with nearly identical genomes found in bones interred side-by-side. Their connections to one another depict a scene of community life, of fatal infection, and perhaps even an ancient epidemic event sweeping through their village.

Take a moment to imagine standing at the excavation site of Nepluyevsky in Russia. Here, an eerie whisper from the past spoke of an outbreak centuries ago, as evidenced by identical S. enterica genomes discovered in adjacent kurgan burials. The Bronze Age souls entombed may have succumbed to an epidemic, demonstrating that time and again, humanity has faced microbial energies causing invasive systemic infections.

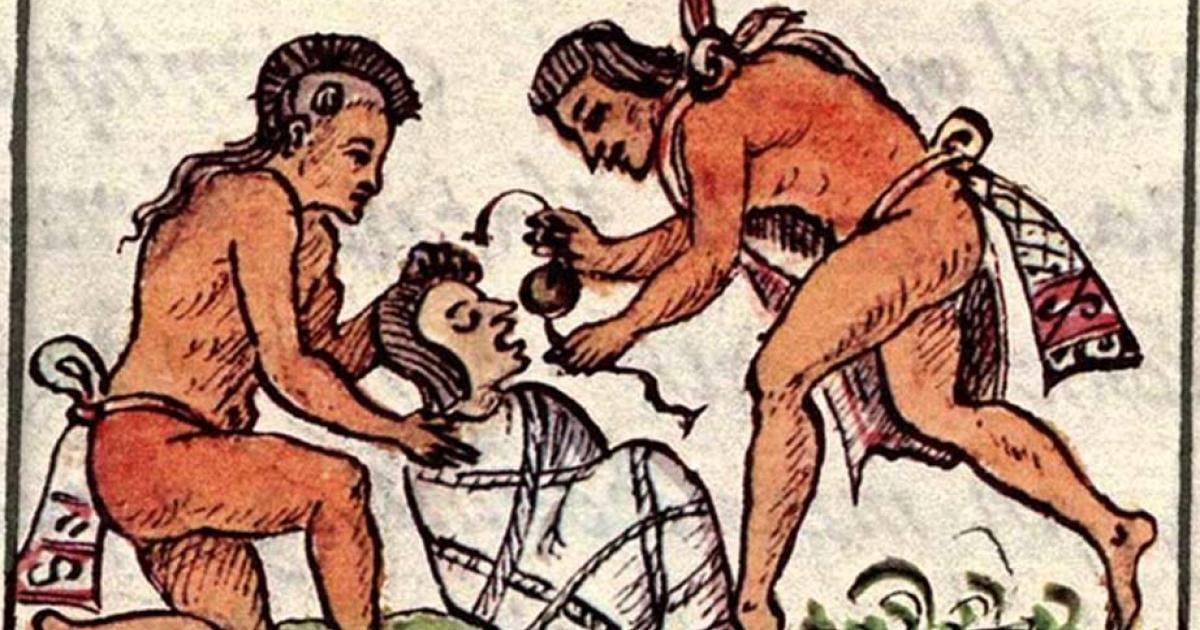

In the mid-16th century, a devastating epidemic called cocoliztli swept through the Aztec population, killing millions. Modern genetic studies of ancient remains suggest the outbreak was likely caused by a strain of salmonella (Salmonella enterica Paratyphi C), which arrived with Europeans and overwhelmed communities that had no prior immunity.

https://www.biorxiv.org/content/10.1101/2025.09.18.676881v1

Discover how your DNA connects to ancient civilizations at www.mytrueancestry.com.

Comments