Kinship and Co‑Burial in Neolithic Sweden

Genetic Kinship and Neolithic Co-burial Rituals on Gotland

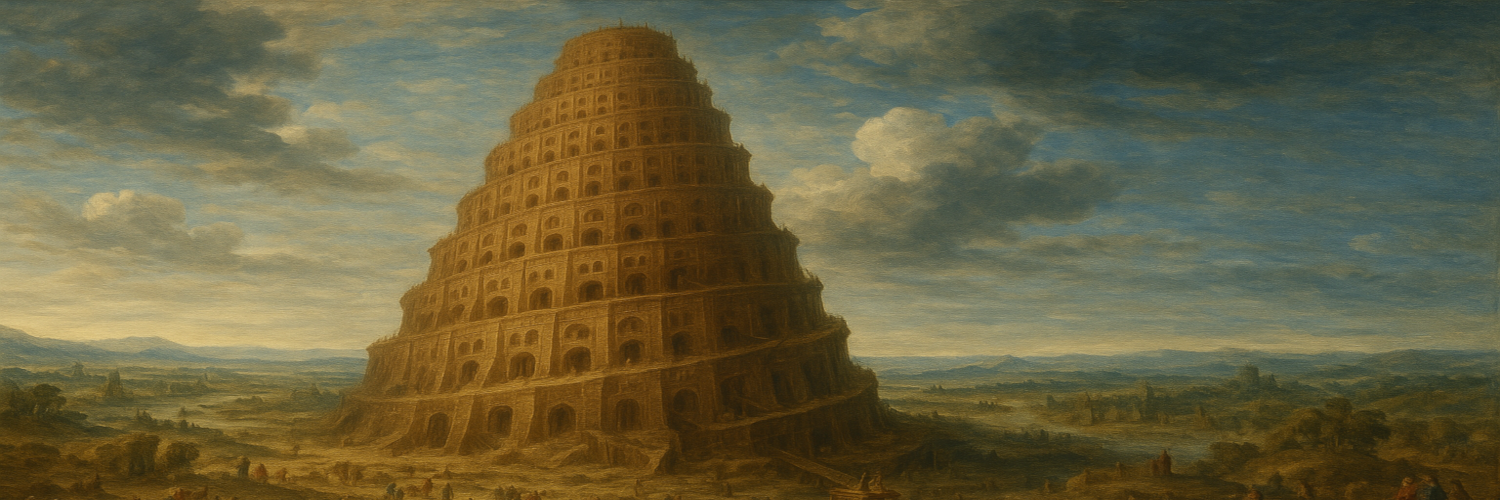

This comprehensive study takes readers to Ajvide on the island of Gotland in the Baltic Sea, one of Stone Age Europe's largest and best-preserved hunter-gatherer cemeteries. Here, people of the Pitted Ware Culture, living around 3400-2200 BCE, buried their dead with extraordinary care and complexity that can now be traced not only in bones and grave goods, but in their ancient DNA. By combining genetic data with detailed archaeological evidence, researchers demonstrate that who was buried with whom was no accident: co-burials at Ajvide were, in effect, carefully planned family graves that reveal the sophisticated social structures of these ancient Baltic communities.

Ajvide was a coastal settlement and burial ground used for centuries by communities who lived primarily from marine resources - seals, fish, and other Baltic Sea life. Excavations have revealed over 70 separate burials, many meticulously documented with detailed records of body position, grave construction, and associated artifacts. Among these discoveries were a small number of particularly intriguing graves containing multiple individuals. These co-burials became the central focus of this groundbreaking study, which applies ancient DNA analysis to understand prehistoric social relationships.

The cemetery represents one of the most significant archaeological sites for understanding late Stone Age hunter-gatherer societies in northern Europe. Unlike many prehistoric sites where burial practices remain mysterious, Ajvide offers an unprecedented combination of well-preserved human remains, detailed excavation records, and now genetic evidence that allows researchers to reconstruct actual family relationships and social structures from over 4,000 years ago.

Statistical analysis reveals a striking pattern across the Ajvide cemetery: of the seven documented multiple burials, six contained at least one child. This frequency far exceeds what would occur by chance, indicating that co-burial practices were strongly associated with children and their extended family networks. This pattern suggests sophisticated burial customs that actively expressed familial relationships through spatial arrangements of the dead.

The research team generated new genetic data from 10 individuals, primarily from co-burials, and combined this with genomes from 24 previously published Pitted Ware individuals from four Gotland sites: Ajvide, Västerbjers, Hemmor, and Ire. The fundamental question driving this analysis was straightforward yet profound: were people buried together actually related by blood?

The results prove remarkable. Every single co-burial examined at Ajvide contained close biological relatives. The genetic analyses successfully distinguished various degrees of relatedness that mirror modern family structures: parent-child relationships, siblings, second-degree relatives such as grandparents and grandchildren or aunts and nieces, and third-degree relatives including first cousins. This precision in identifying ancient family relationships represents a significant advancement in archaeological genetics.

Burial 23 contained an adult man (ajv23a) and a young person (ajv23b) aged 12-13 years. While earlier osteological analysis had suggested the child might be male, genetic testing revealed she was female. DNA evidence demonstrates a clear parent-offspring relationship between them. Their different maternal mitochondrial lineages rule out the possibility of the girl being the man's mother, confirming that he was her father.

Archaeological evidence adds compelling depth to this relationship. The man's bones were disarticulated and bundled, indicating he had died earlier, perhaps elsewhere, and his remains were subsequently gathered and reburied alongside his daughter. This grave preserves not merely a biological connection, but a consciously remembered and honored relationship. Someone in the community ensured that father and daughter were ultimately reunited in death, suggesting sophisticated concepts of family continuity and memorial practices.

Burial 29 presents one of the most emotionally evocative scenes at Ajvide. An adult woman (ajv29a), aged approximately 20-30 years, was buried with two children positioned in her arms: a boy of about 4 years (ajv29b) and a girl around 2 years old (ajv29c). The arrangement initially suggests a mother with her children, but genetic analysis reveals a more complex family structure.

DNA testing shows that the two children were full siblings sharing the same maternal lineage, while the adult woman carried different maternal DNA, definitively ruling her out as their biological mother. Instead, she was their close paternal relative, most likely an aunt or half-sister. Previous isotope analysis had indicated this woman had not breastfed the younger child, which now makes perfect genetic sense. Yet the burial arrangement - both children nestled protectively in her arms - clearly identifies her as a primary caregiver in death and presumably in life.

This burial provides compelling evidence for extended family child-rearing practices and possibly formal fostering arrangements within Pitted Ware society. The careful positioning suggests this woman held significant responsibility for these children despite not being their birth mother, revealing sophisticated kinship systems that extended well beyond nuclear family units.

Burial 52 contained a boy of approximately 7 years (ajv52a) and a very young girl of about 1.5-2 years (ajv52b). Osteological and isotopic evidence indicates they were buried simultaneously, suggesting they died around the same time. Genetic analysis identifies them as third-degree relatives, equivalent to relationships like first cousins or great-niece and great-uncle.

Given both individuals died as children, certain relationship possibilities like grandparent-grandchild can be eliminated based on age. While the exact familial connection cannot be determined more precisely, they clearly belonged to the same extended family network. This burial demonstrates how even more distant family relationships were considered significant enough to warrant shared graves, indicating the importance of broader kinship ties in Pitted Ware society.

Burial 79 tells a particularly poignant story of remembered relationships spanning years or possibly decades. A young woman (ajv79b), aged about 18-20, was buried with a girl of 7-9 years (ajv79a). The adult skeleton showed signs of disturbance and bundling, indicating secondary burial, while radiocarbon dates suggest the two individuals may not have died simultaneously.

Genetic analysis identifies them as third-degree relatives, similar to first cousins or great-aunt and niece relationships. Most significantly, despite the temporal separation of their deaths, their family relationship was remembered well enough that community members ensured they were eventually buried together. This practice reveals remarkable social memory and commitment to maintaining family connections that transcended death itself.

Analysis of all co-burials at Ajvide reveals that children were central to these special burial practices. The overwhelming presence of children in multiple graves suggests that when a child died, the community often chose to place them with relatives in graves that physically expressed their position within extended family networks. These were not merely practical group burials but deliberate statements about belonging, kinship, and social identity.

This pattern indicates that Pitted Ware society placed particular importance on children's relationships with extended family members. The careful placement of children with aunts, cousins, or other relatives suggests sophisticated understanding of kinship networks and possibly special concern for ensuring children were not alone in death, even when parents were unavailable or had been buried elsewhere.

These genetic findings gain additional significance when viewed within the broader archaeological context of Pitted Ware burial practices on Gotland. Previous studies have documented the rich material culture associated with these burials, including distinctive pottery, flint tools, amber ornaments, and animal bones, particularly from seals and other marine species.

The bundled, secondarily buried adults in graves 23 and 79 suggest that relatives could be moved, curated, and eventually reburied to bring them "home" alongside younger family members. Such practices hint at ongoing relationships with the dead and active efforts to maintain kinship connections across time and space. These secondary burials required significant community effort and organization, indicating the high value placed on family continuity.

The treatment of bodies and grave goods reveals a society with sophisticated concepts of memory, identity, and social obligation. The effort required to locate, exhume, and rebury individuals alongside specific relatives demonstrates remarkable social cohesion and shared commitment to family structures that extended beyond individual lifespans.

Comments