Genetic Diversity in the Late Iron Age Goths of the Masłomęcz Group

Gothic Cosmopolitanism and Long-Range Mobility beyond the Roman Frontier

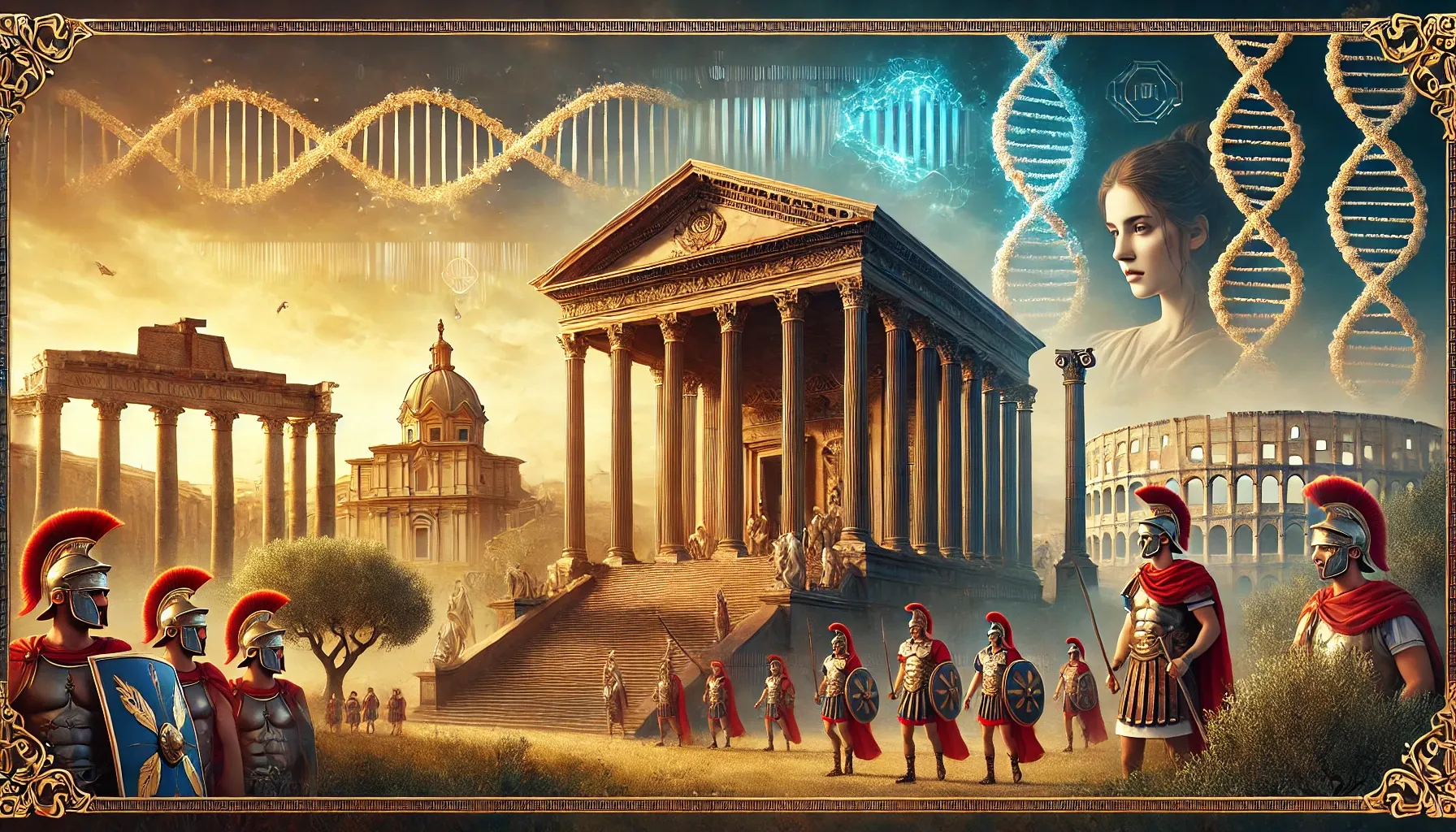

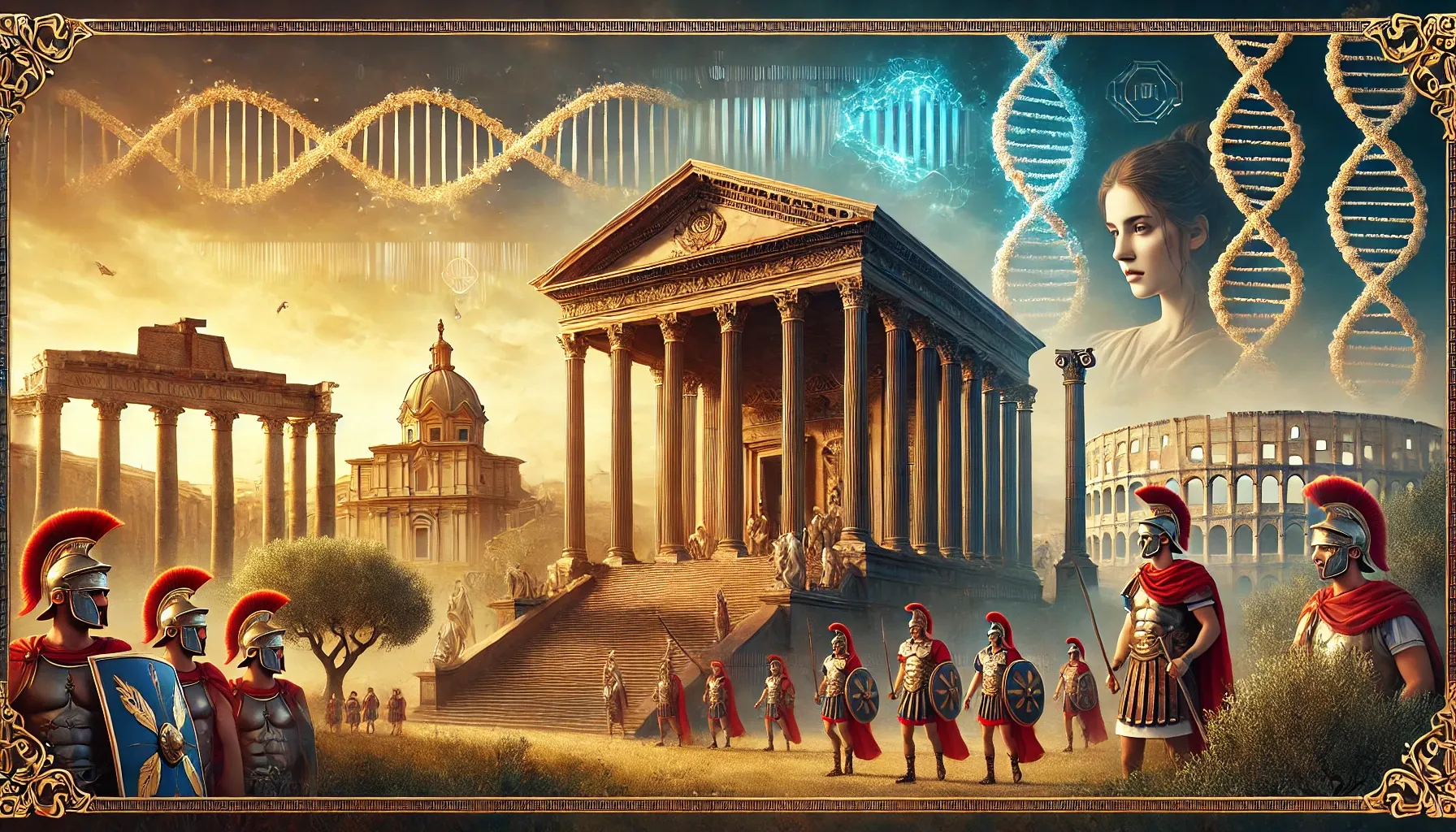

This comprehensive study transports readers to the eastern fringes of the Roman world, into the Hrubieszów Basin of what is now eastern Poland, where an astonishingly rich Goth-associated community – the Masłomęcz group – flourished between the 2nd and 4th centuries CE. Far from being an isolated barbarian backwater, this community emerges from archaeological and genetic records as a remarkably connected, cosmopolitan hub, drawing in people and objects from Scandinavia, the Baltic, the Balkans and even the wider Mediterranean world.

The Masłomęcz group takes its name from a large cemetery at Masłomęcz, one of roughly 70 settlements and 10 cemeteries scattered along the Hrubieszów Basin, east of the modern city of Zamość. This region, lying well beyond the Roman frontier, formed part of the wider Gothic cultural complex that had its roots in the Baltic Sea zone and expanded south-eastwards towards the Black Sea. Archaeologists long ago noticed that the material culture here did not look provincial but sophisticated and interconnected. Gold coin hoards such as the Metelin treasure, a sword fished from the Bug River near Gródek, and rich assemblages of jewelry and dress fittings from dozens of sites point to intense participation in long-distance trade and diplomacy.

The cemeteries at Masłomęcz 15 and Gródek 1C alone have yielded over 800 graves, many furnished so abundantly and so precisely datable that they form a chronological backbone for the local Iron Age. These burial grounds reveal a funerary world that is anything but simple or uniform, with graves containing rich inventories of brooches, belts, beads, and weapons, some clearly imported or copying foreign fashions.

The graves themselves are as striking as their contents, displaying remarkable diversity in burial practices. Bodies might be incomplete, graves reopened, extra bones – even skulls – added later, and children buried with isolated adult bones. Multiperson burials are common, creating a complex archaeological landscape that speaks to sophisticated ritual practices and social organization.

The grave goods themselves draw lines outwards across Europe. Some burials follow Sarmatian nomadic fashions familiar from the steppe, others echo Baltic traditions, and yet others display links to the Sântana de Mureş culture closer to the Black Sea. The evidence makes clear that people in the Hrubieszów Basin were not shy about adopting, blending and reworking foreign styles, creating a unique material culture that reflects their cosmopolitan connections.

Ancient DNA analysis allows researchers to track not just styles, but actual people. From 37 newly sequenced individuals, combined with already published data, emerges a portrait of a population heavily rooted in Scandinavian ancestry, yet studded with striking outliers whose genomes point to diverse homelands across Europe and beyond.

A dominant theme is the strong Scandinavian signal, particularly in male lines. Most genetically male individuals carry Y-chromosome types today most common in Scandinavia, especially a lineage known as I1, attested in northern Europe since the Bronze Age. One young male bears a sub-branch of the R1a lineage largely restricted today to Scandinavians and Viking-age contexts. Yet even among men the picture is not uniform. A handful of males carry lineages associated with later Slavic and Baltic populations, others hint at western European connections, and at least one has a Y-chromosome type linked today to the Balkans.

The number of distinct male lineages is remarkably high, suggesting that the community was not founded by one tight-knit clan, but by a broad, mixed group of unrelated men. This genetic diversity points to a founding population drawn from multiple sources rather than a single migrating tribe.

Several individuals stand out as particularly compelling examples of long-distance mobility. Individual PL085, buried in Masłomęcz 15 in the early phase of the cemetery (late 2nd century CE), carries genetic markers pointing strongly towards the Mediterranean and Balkans. His presence belongs to the very beginnings of the Masłomęcz sequence, implying that outsiders from southern regions were part of the story from almost the first chapter.

Another early-dated individual, PCA0110, stands even further toward Mediterranean populations in genetic space, representing evidence of long-range mobility likely involving contacts reaching deep into the Roman world or its borderlands. This southern-leaning ancestry appears early, reinforcing the idea that the Masłomęcz group did not slowly open up to the wider world, but was born cosmopolitan.

At the burial ground of Strzyżów, individual PL046 shows strong genetic similarities to Iron Age and Roman-period western and central European populations, with ancestry models requiring an additional component pointing toward south-eastern Europe. This grave contained an artifact so far unique in the region, with parallels only in the Balkans, suggesting this was not just a Goth imitating Balkan fashion, but someone whose family history genuinely extended into those southern landscapes.

The Masłomęcz group sits geographically not far from the Baltic coast, and genetic data firmly support close contact with Baltic groups. Several individuals carry ancestry patterns most similar to Iron Age and Roman-period populations in what is now Lithuania and the eastern Baltic. These genetic signatures match patterns already glimpsed in grave goods, with Baltic ornament types appearing in Masłomęcz graves from the 3rd century CE onwards.

Not all non-local ancestries point north or south. A set of individuals carry genetic signatures most similar to Iron Age and Roman-period populations from western and central Europe, including regions corresponding today to Germany, Czechia, Austria, and even Britain and Portugal. These patterns suggest that people whose recent ancestry lay around the Rhine, the Alps, or even the Atlantic seaboard could, within a few generations, find their descendants buried among Goths in the Hrubieszów Basin.

Despite such mobility and mixing, the community shows interesting patterns of social organization. Genetic analysis reveals that identity and burial practice in this Goth-associated society cannot be reduced to simple family trees. Among fifty genetically analyzed individuals, only one clear first-degree relationship appears: a father-daughter pair. Even individuals buried together often show no close genetic relationship, suggesting that shared graves and ritual arrangements followed social logics beyond straightforward biological relatedness.

The community was large enough, and its marriage practices broad enough, that close inbreeding was avoided in almost all cases. This points to a substantial, open population that actively incorporated newcomers while maintaining social cohesion through means other than tight kinship networks.

Perhaps the most striking implication of this research is how normal long-distance movement appears once the genetic evidence is examined. The community at Masłomęcz, sitting far beyond Rome's formal frontier, nonetheless attracted individuals whose ancestors had connections to Balkan towns, Baltic forest settlements, Italian cities, steppe camps, and central European settlements.

Genetic modeling reveals a complex ancestry pattern: a strong core tracing back to early Iron Age Scandinavia, consistent with traditional views of Gothic origins around the Baltic Sea; additional components from Baltic, central and eastern European Bronze and Iron Age populations; clear contributions from Balkan and Mediterranean groups, sometimes linked to Dacians, Thracians or mixed Greek-Roman cities along the Black Sea; and traces of steppe-related ancestry, compatible with Sarmatian connections already inferred from horse equipment and other steppe-style artifacts.

When researchers map the most likely geographic center of each person's ancestry, the Masłomęcz cemeteries become nodal points in a network radiating out to Pomerania, the Baltic states, the Balkans, Italy, and western-central Europe. Some individuals appear local – their ancestry already blended into the Hrubieszów Basin – but others still carry clear signatures of distant origins.

Comments