Erik the Red and the First Viking Settlers of Greenland

Erik the Red and Norse Greenland: From Sagas to Archaeological Evidence

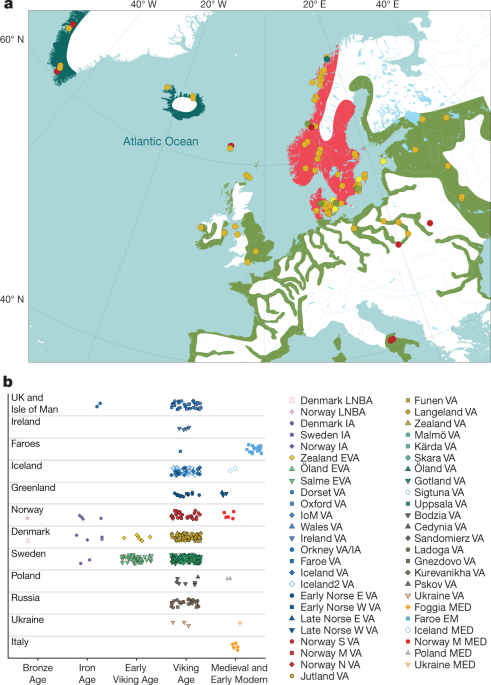

The story follows Erik the Red as he transforms disgrace into opportunity. Cast out of Iceland in 982 CE for a series of violent feuds, Erik does not simply lie low. Instead, he sails west with fellow exiles to investigate rumors of a vast, icy land once glimpsed by earlier seafarers. During his three-year exile he explores the fjords of what he will later call "Greenland," carefully noting where grass grows, where animals can graze, and where farms might cling to the edges of the ice. When his exile ends, the sagas say, Erik returns to Iceland not as a broken man but as a salesman of dreams. He paints this new land in tempting colors, even choosing the friendly name "Greenland" to lure settlers. Around 985 CE he departs again, this time at the head of a true migration: some twenty-five ships leave Iceland, though nearly half are lost on the crossing. Those who survive settle around two main areas on Greenland's southern coast, the Eastern and Western Settlements, with Erik himself establishing his great farm at Brattahlið in Eriksfjord.

When we read about vanished civilizations, it’s easy to forget that their descendants still walk among us. If you’re curious which of them you might share roots with, you can explore your own genetic links at www.mytrueancestry.com.

In the saga tradition, Brattahlið (meaning "steep slope") is no ordinary farm. It is a seat of power, the home of a man who styles himself chieftain of Greenland. Here Erik's household grows: his son Leif Erikson, later famed as the explorer of North America, and his daughter Freydis, remembered as fierce and uncompromising, are among the figures the sagas cluster around this estate. The sagas also describe a religious revolution unfolding at Brattahlið. Erik's wife, Thjodhild, converts to Christianity and insists on building Greenland's first church beside the farm. She will not share Erik's bed until the new faith has a home on his land. Brattahlið thus becomes a stage on which old Norse gods and the new Christian order contend within one family, under one roof.

All of this rests on stories written down centuries after the events they describe. The crucial question emerges: does the ground of Greenland agree with the ink of the sagas? To answer this, we turn to Qassiarsuk, a modern village on the shore of Eriksfjord, widely believed to sit where Brattahlið once stood. Early in the 20th century, scholars began to poke at the grassy slopes here, finding scattered bones and scraps of cloth but nothing to match the saga's grand farm. The turning point came in 1926, when Danish researchers Poul Nørlund and Aage Roussell opened a mysterious trapezoid coffin in Qassiarsuk. It was empty, but persistence paid off. Nearby they discovered a grave containing human remains and a stone carved with runes, an unmistakable Norse calling card. In 1932, a larger expedition returned, led by Nørlund with Swedish archaeologist Mårten Stenberger. This time they dug in earnest. Out of the turf and stone emerged a small Norse world: at least 18 structures, ranging from dwelling houses and barns to storehouses and a church. The layout, the building techniques, and the careful positioning on good grazing land all fit what is known of Viking Age farming in the North Atlantic.

These ruins come to life when examined closely. The longhouses and outbuildings at Qassiarsuk are not just stone outlines; they are the ghostly floorplan of daily work. Thick turf walls once held in heat during fierce winters. Barns sheltered cattle, sheep, and goats whose bones now fill the site's ancient rubbish heaps. Storehouses guarded precious hay and trade goods. One intriguing feature is the evidence for visitors. Alongside the farm buildings, archaeologists uncovered low turf and stone structures they interpret as shelters for guests and temporary residents, along with simple tent rings and hearths. This has led to the tantalizing suggestion that Qassiarsuk may have doubled as an assembly place, an "all-thing" for Greenlanders, where laws were recited, disputes settled, and news traded. Written sources later mention lawmen based at Brattahlið, lining up neatly with what the spades have found.

The ground at Qassiarsuk preserves a clash of faiths as vividly as any saga. Among the finds is a humble but potent object: a whetstone engraved with Thor's hammer. It is a small thing, something a farmer or craftsman might carry in a belt or pouch, yet it signals a stubborn loyalty to the old Norse gods in this remote colony. Yet nearby lie the remains of a church whose existence points firmly in the other direction. Nørlund and Stenberger uncovered a small stone-and-turf church here in the 1930s. Its construction date is later than Erik's lifetime, which complicates the link to the saga's story of Thjodhild's early conversion. Can Brattahlið truly be Brattahlið without Thjodhild's original church? This question shows how saga and archaeology sometimes rub awkwardly against each other. The sagas promise an early church at Erik's home; the ground gives us a later church in the same area. The two are related, but not identical.

Some of the most revealing evidence comes not from grand buildings but from ancient rubbish, specifically the middens, or trash heaps, near the farms. In 1932, excavators at Qassiarsuk dug into a dense deposit of animal bones and kitchen waste. These remains tell us what the settlers ate, hunted, and herded. Seal bones are everywhere: harp seals, harbor seals, and others, showing that seal hunting was central to survival. Caribou bones appear too, proof that the Norse did not ignore Greenland's land mammals. Mixed in are the remains of cattle, sheep, and goats, animals brought from across the sea to provide milk, meat, and wool. Chemical analysis of these bones and of human remains from Norse Greenland shows how diets shifted over time. As conditions grew harsher, people relied more on marine foods, seals and fish, especially in the Eastern Settlement where Qassiarsuk lies. It seems the Greenland Vikings slowly turned from land farmers into part-time sea hunters, adapting to their challenging landscape even as they clung to familiar farming routines. The walrus also played a particularly profitable role. Far to the north in Disko Bay, Greenland's Norse encountered impressive herds of these tusked creatures. Walrus ivory became a valuable export to Europe, and tusks from Greenland fed the taste for luxury carvings in distant churches and courts.

Another dramatic archaeological moment came much later, in 1961, when construction workers in Qassiarsuk accidentally exposed human skulls while preparing foundations for a school hostel. The bones were quickly recognized as medieval, and professional excavations followed. What they uncovered looked uncannily like the church described for Thjodhild in the sagas. Archaeologists dug out a small turf church and an adjacent cemetery. Around 155 graves were carefully recorded and removed. The burials themselves offer a glimpse into the community's beliefs and social organization. Men and women were separated in death: women were buried on the north side of the churchyard, men on the south. This ordered division around the church hints at a community strongly shaped by Christian ideas of ritual space and proper burial. Radiocarbon dating of a sample of the skeletons placed them roughly between the years 1000 and 1200 CE. That date range makes the site an excellent candidate for the first Christian generation in Greenland, the very time when the sagas place Thjodhild and her church. Many scholars now feel reasonably confident that this modest little building may indeed be "Thjodhild's Church" or at least the church that later storytellers remembered under her name.

The saga of Erik the Red ends as dramatically as it begins. Around 1003 CE, another wave of settlers arrived in Greenland, and with them, unseen companions: new diseases. According to tradition, an epidemic swept through the colony, and Erik himself fell victim. This makes him one of the last truly legendary figures of the Viking Age, dying on the very edge of the known world. Archaeology has yet to identify his resting place. No grave marker naming Erik, no chieftain's burial filled with grand grave goods, has been found at Qassiarsuk. If he lies there, he is among the anonymous dead in the churchyard or in an unmarked grave somewhere on the surrounding slopes. A man whose fiery temper and daring voyages reshaped the map of the North Atlantic now vanishes into the earth without a trace we can firmly pin to his name.

The Norse settlements in Greenland faced mounting challenges as the medieval period progressed. From the 13th century onwards, the North Atlantic climate began to cool significantly. This climatic shift, sometimes called the "Little Ice Age," brought longer winters, shorter growing seasons, and increased sea ice that made navigation treacherous. The thick turf walls and stone foundations visible at Qassiarsuk today speak to buildings designed for harsh conditions, but even these adaptations had limits. Archaeological evidence shows that farms were gradually abandoned, with buildings left unrepaired and fields surrendered to frost. The animal bones in later middens tell the story: fewer cattle and sheep, more seals and marine resources. The Norse were adapting, but the land was becoming less hospitable to their traditional way of life.

Alongside climate change came economic pressures that slowly strangled the Greenland settlements. The lucrative walrus ivory trade that had once connected these remote farms to European markets began to decline. African elephant ivory, imported through new southern trade routes, flooded European markets and made walrus tusks less valuable. The Black Death of the 14th century devastated Norway and Iceland, the settlements' primary trading partners, further reducing contact with the outside world. Archaeological evidence from the later phases of Norse occupation shows fewer imported goods, more makeshift repairs to buildings, and signs of increasing isolation. The harbors that had once welcomed ships loaded with European trade goods fell silent.

As the Norse settlements declined, new inhabitants were moving into the Arctic. The Thule people, ancestors of modern Inuit, had been migrating eastward across the Canadian Arctic for centuries. These skilled hunters brought technologies and survival strategies perfectly adapted to the changing climate: kayaks for ice-filled waters, sophisticated ice hunting techniques, and a mobile lifestyle that could follow seasonal resources. While Norse farms fell silent, Thule winter houses and hunting camps became increasingly common across Greenland. The transition was not violent conquest but rather environmental succession - one culture fading as another, better adapted to the new conditions, took its place.

Discover how your DNA connects to ancient civilizations at www.mytrueancestry.com.

Comments