Medieval DNA and Isotope Evidence for the Local Origins of Berlin’s First Townspeople

Medieval Berlin: Archaeological and Genetic Evidence from St. Peter's Churchyard

The origins of Berlin emerge not from dusty chronicles or royal charters, but from thousands of graves discovered beneath the bustling streets of modern central Berlin. At the former churchyard of St. Peter's in medieval Cölln, situated on an island in the River Spree, archaeologists uncovered 3,221 graves containing 3,778 individuals. Among these lay the very earliest burials, dating from around 1150 to 1349, predating the first written mention of Berlin itself by several decades.

These earliest skeletons belong to the founding population of Cölln, one of the twin medieval settlements that later fused into the city known today as Berlin. Berlin sat on one bank of the Spree, while Cölln occupied the opposite shore. This cemetery serves as an extraordinary time capsule, allowing researchers to investigate fundamental questions: who were these people, where did they come from, and how did a small riverside market grow into a major urban center?

When we read about vanished civilizations, it’s easy to forget that their descendants still walk among us. If you’re curious which of them you might share roots with, you can explore your own genetic links at www.mytrueancestry.com.

Between 2007 and 2009, construction work in central Berlin opened an unprecedented window onto the medieval past. Under the direction of archaeologist Claudia Melisch, St. Peter's churchyard was excavated using meticulous modern methods. Each grave was recorded individually, photographed, surveyed, and in selected cases even scanned using 3D laser technology. A digital version of the classic Harris matrix, an archaeological tool for plotting stratigraphic layers and temporal sequences, allowed researchers to assign each burial to specific 50-year time periods.

From the thousands of interments discovered, the study focused on just over a hundred skeletons from the earliest phases of burial activity. Many bones had been stained dark by groundwater infiltration and were partially dissolved by centuries of soil chemistry. However, genetic material preserved in teeth and dense ear bones survived remarkably well, enabling the research team to construct a detailed biological portrait of the community that occupied Cölln during its first two centuries of existence.

The earliest burials at St. Peter's form a vivid cross-section of a burgeoning medieval town, rather than representing a select group of monastic elites or noble families. Men and women are both well represented in the sample, with approximately 54 men and 42 women identified. All age groups appear in the burial population, ranging from young children to adults estimated to have reached 50-60 years of age at death. Even several children buried among the earliest settlers yielded sufficient DNA preservation to allow researchers to determine their biological sex through genetic analysis.

When the research team compared genetic profiles across all 96 individuals studied, they discovered a remarkable pattern: no close biological relatives could be identified among any of the studied individuals. No obvious parent-child pairs, siblings, or grandparent-grandchild relationships were detected. Even individuals buried together in the same grave contexts, known as multiple burials, proved not to be closely related through blood ties. This early Cölln community was evidently not composed of a cluster of extended families transplanted as a single group from elsewhere. Instead, it appears to represent an assemblage of individual migrants including men, women, and children who had independently converged on this new commercial hub along the Spree River.

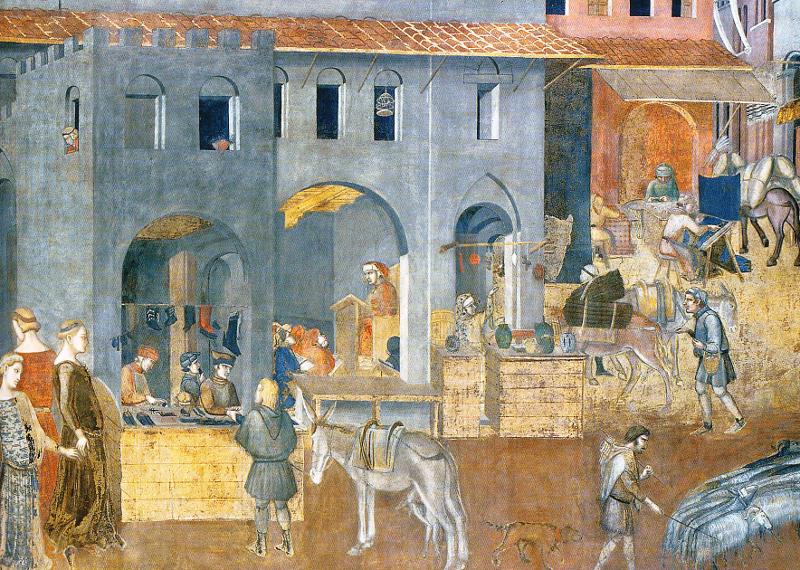

St. Peter's served as the oldest church in Cölln, ministering to a settlement that began around 1150 and continued to bury its dead in the associated churchyard until 1717. By that later date, Berlin and Cölln had long since unified into a major Prussian capital. The graves that form the focus of this study belong to the first 200 years of the churchyard's use, roughly spanning 1150-1349. These individuals lived during a crucial transitional period when the surrounding region was shifting from an Elbe Slavic cultural landscape to a dense, market-oriented, German-speaking urban environment.

Written documents remain almost entirely silent regarding this earliest developmental phase of the settlement. The archaeological and genetic evidence from the graves, however, speaks eloquently through analysis of bones, teeth, and burial contexts. This interdisciplinary approach allows researchers to reconstruct both the social composition and geographic origins of the founding community, providing insights into urban development that precede the establishment of written archives by many decades.

To understand the ancestral origins of Cölln's founding population, researchers analyzed two distinct categories of inherited genetic markers that provide different perspectives on population history and migration patterns.

Analysis of mitochondrial DNA, which is inherited exclusively through the maternal line, revealed that all 96 individuals displayed maternal lineages fitting comfortably within classic West Eurasian, and more specifically European, genetic patterns. Nearly half of the studied individuals carried the extremely common European maternal lineage designated as haplogroup H, with various subtypes that closely match those observed in present-day central European populations. Another substantial portion of the population belonged to haplogroup U and its various subtypes, including U5, which is frequently described as one of the most ancient European maternal lineages, likely tracing back to Paleolithic hunter-gatherer populations.

Additional maternal lineages identified in the sample include haplogroups T, J, and K, appearing at frequencies that more closely mirror present-day German populations than contemporary Slavic populations located further to the east. Particularly noteworthy is the relatively high proportion of haplogroup K individuals, matching modern German demographic patterns while significantly exceeding typical frequencies observed in Polish or other Slavic population samples.

Modern Slavic populations sometimes contain small fractions of maternal lineages showing East Asian genetic connections, reflecting ancient migrations and population mixing events. These distinctive eastern lineages are completely absent from the Cölln sample. While the researchers emphasize that maternal lineages alone make it challenging to distinguish clearly between medieval Germanic and western Slavic populations, given the region's long history as a genetic crossroads, the specific pattern observed at St. Peter's aligns most closely with a broadly central European demographic profile rather than a distinctly eastern Slavic genetic signature.

Analysis of Y-chromosome data from 54 men provides an even clearer picture of population origins and affinities. Three major paternal lineage patterns dominate the sample and reveal important demographic insights about the founding population's composition and likely geographic origins.

The most frequent paternal lineage belongs to haplogroup R1b, identified in 24 of the 54 men studied, representing 44.4% of the male population. Within this group, the majority carry specific sublineages U106 and U198, which today achieve their highest frequencies in regions along the Rhine River, parts of the Low Countries, southern Scandinavia, and various areas of Germany. These lineages are often associated with ancient Germanic populations and their historical heartlands located west and northwest of the study region.

Almost equally numerous are men belonging to haplogroup R1a, found in 17 of the 54 males, representing 31.5% of the sample. This lineage displays the opposite geographic distribution pattern compared to R1b, being very common in Poland and other Slavic-speaking countries while becoming progressively less frequent in western Germany and dropping to even lower levels toward the Atlantic coast. All R1a men at St. Peter's belong to two specific branches: M458 and M558, both strongly associated with Central and Eastern European populations and commonly found among modern Slavic-speaking groups.

The third major category consists of haplogroup I, present in ten men including six I1 and four I2a individuals. This represents a characteristically European set of Y-chromosomes rarely encountered outside the continent, often interpreted as descending from some of Europe's earliest hunter-gatherer populations. The I1 men belong to branches widespread in northern Europe today, particularly Scandinavia, while also being common throughout Germany.

Additional paternal lineages appear in single individuals, including J2a, G, and T. While these lineages occur at lower frequencies, they are well-documented in modern German populations and often trace deeper ancestral roots to Mediterranean, Near Eastern, or Caucasian regions, likely reflecting the medieval town's integration into broader trade and migration networks.

When researchers compared the complete Y-chromosome profiles from Cölln with modern European populations using statistical analysis, the medieval sample aligned most closely with present-day Germans and Czechs. The ancient population showed significant statistical differences from modern Polish and Russian samples to the east, as well as from British, Dutch, and Danish populations to the west and north. This demographic pattern suggests that the founding male population of Cölln already exhibited genetic characteristics strikingly similar to contemporary central European populations, particularly those found in the modern Berlin-Brandenburg region.

Beyond genetic ancestry, the research team investigated where specific individuals actually spent their childhoods through chemical analysis of tooth enamel. This approach provides insights into personal life histories and migration patterns that complement the longer-term ancestral information revealed through DNA analysis.

Tooth enamel forms during specific periods of childhood and permanently incorporates chemical signatures reflecting the local environment where an individual lived during tooth development. Two key chemical indicators were analyzed to determine geographic origins and detect evidence of migration or mobility during the medieval period.

Strontium isotope ratios in tooth enamel reflect the underlying geological characteristics of the region where an individual consumed food and water during childhood. Different rock types and soil compositions produce distinctive strontium signatures that become incorporated into developing teeth through the food chain. Oxygen isotope ratios vary systematically with altitude, distance from coastlines, and regional climate patterns, providing complementary information about probable geographic origins.

Analysis of 66 early burials revealed distinct patterns of local residence and regional mobility among Cölln's founding population. Approximately two-thirds of the individuals displayed strontium values falling squarely within the range typical for Berlin and the surrounding Brandenburg plain. These individuals were almost certainly locals who were born and raised in or very near the developing settlement, representing a substantial core of regionally-rooted residents.

A significant secondary group showed strontium values slightly elevated above the local Berlin range, with signatures pointing to nearby upland regions in central Germany. These areas include locations such as the Thuringian Basin, the Thuringian-Franconian Slate Belt, or other regions situated west and southwest of Berlin. Many of these individuals were buried between 1200 and 1249, suggesting that as Cölln's commercial importance expanded, the settlement increasingly attracted migrants from a widening geographic catchment area spanning several days' travel from the town.

A much smaller subset of individuals displayed distinctly higher strontium values that exceed expectations for any nearby regions, indicating probable origins in mountainous or geologically distinctive areas. These signatures point toward regions such as the Harz mountains, the Erzgebirge-Fichtelgebirge range, or the Lusatian Block. Supporting oxygen isotope values, typically lower at higher elevations, reinforce interpretations that some of Cölln's early residents had spent their childhoods in upland landscapes before migrating northeastward along established trade and migration corridors.

At the opposite end of the spectrum, three women exhibited strontium values slightly below Berlin's local range, pointing instead toward the northwestern portion of the North German plain. These individuals appear to represent migration from northern and western directions, demonstrating that Cölln attracted settlers from multiple geographic directions rather than following a single predominant migration stream.

For 18 individuals, researchers analyzed multiple teeth per person, typically including the first molar formed from birth to approximately age four, and later-developing teeth such as second and third molars. This approach enables reconstruction of possible movements and residential changes during different phases of childhood and adolescence, providing unusually detailed insights into individual life experiences in the medieval period.

Eleven individuals, comprising six men and five women, showed matching strontium values across all analyzed teeth. Six of these displayed consistent local Berlin signatures, indicating they were born, raised, and remained in the Cölln area throughout their youth and into adulthood. Four additional individuals showed consistent but non-local chemical signatures, suggesting they grew up elsewhere in regions with elevated strontium levels and migrated to Berlin only later in life, prior to their deaths and burial at St. Peter's.

Seven individuals provided clear evidence of geographic mobility during childhood and adolescence. Four men showed local Berlin-area signatures in their earliest-forming teeth while later-developing teeth carried slightly higher strontium values, suggesting they moved from the immediate Cölln region to nearby areas with different geological characteristics during childhood, possibly returning as adults to the town where they were eventually buried. Two others demonstrated more dramatic shifts, moving from regions with already elevated strontium signatures to areas with even higher values during adolescence, before ultimately arriving in Berlin for burial. One individual showed movement in the opposite direction, transitioning from a high-strontium region toward the Berlin area during childhood or youth.

These detailed chemical life histories reveal that medieval Berlin and Cölln were characterized by considerable individual mobility rather than representing static residential communities. Children and adolescents regularly moved between urban and rural environments and among different regions within the broader central European landscape, challenging modern assumptions about medieval residential stability and demonstrating that geographic mobility was a normal aspect of life centuries before modern transportation and communication technologies.

The isotopic analysis extended beyond human remains to include six animals found within the cemetery contexts: pigs, cattle, and sheep or goats. These animal teeth displayed very high strontium values combined with particularly low oxygen isotope signatures, placing them far outside the expected range for the local Berlin area. The chemical signatures indicate these animals were raised in mountainous regions and subsequently transported to Cölln, most likely as livestock for slaughter or as meat for consumption.

This evidence provides important insights into Cölln's economic integration within broader regional trade systems. Even during the 12th and 13th centuries, the emerging Berlin-Cölln settlement was already connected to supply networks extending across central Europe, bringing both people and goods from highland regions to the developing river port. The presence of mountain-raised livestock suggests established trade relationships and transportation corridors linking the North German Plain with more distant upland economies, demonstrating the early commercial sophistication of this medieval trading center.

Discover how your DNA connects to ancient civilizations at www.mytrueancestry.com.

Comments