Mantiot Greeks - A Possible Spartan-descendant Identity?

Deep Maniot Y‑Chromosome Lineages and Their Ancient Mediterranean Connections

This comprehensive study takes readers deep into the rugged spine of the Mani peninsula, revealing how the Y‑chromosomes of its men carry traceable echoes of Bronze Age warriors, Roman soldiers, Anatolian migrants, Punic traders, and steppe horsemen. Rather than being an isolated backwater, Deep Mani emerges as a crossroads where lineages from the Balkans and West Asia were absorbed, localized, and then jealously guarded within tight clan systems that persist to this day.

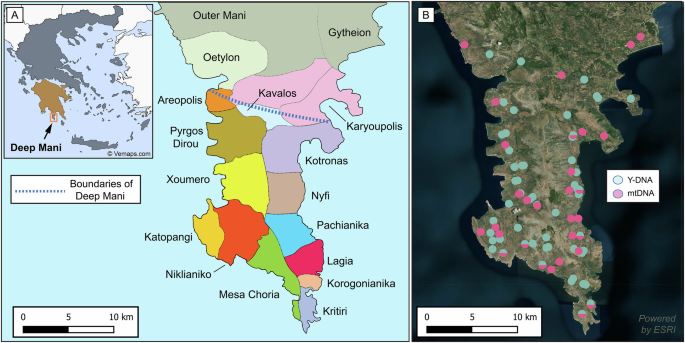

Several Maniot Y‑lineages demonstrate close relationships to men buried in Roman and Byzantine Balkans, and to populations of western Anatolia and the Levant. One branch found at a notable 7% frequency in Deep Mani, labeled J‑PH4244, centers on Pyrgos Dirou–Areopolis and the northern border of Deep Mani. Genetically, this branch shares a deeper ancestor with a Byzantine‑era man buried in western Anatolia, dated to around 2,500 BCE at the level of their common ancestor. This lineage probably reached Deep Mani during the Roman period, carried by men moving between Anatolia and the southern Peloponnese.

Other Maniot lineages sit on branches that also appear in Roman‑period graves from the Balkans. One Maniot branch relates to a man from Muğla whose shared ancestor is dated around 2,150 BCE, pointing to long‑standing connections between western Anatolia and the Balkans. Another Maniot lineage matches exactly a Roman‑period individual from Sisak Pogorelec in Croatia, tying Deep Mani to a Roman frontier community in the northwestern Balkans. A third links to an individual buried near Osijek in Croatia, who carried a variant of Y‑chromosome group G. Present‑day Deep Maniots share a younger branch of this same line, implying that whatever male migration brought these men to the Roman Balkans also left lasting marks in Mani.

Archaeologically, these connections align with the known role of the Mani coast in the Roman and Byzantine world. Places such as Caenipolis received immigrants from across the Greek‑speaking east – from Cyprus, Judea, and beyond – and these incoming men brought patrilineal lines still detectable in Maniot surnames today. The dense network of Roman forts, towns, and roadside settlements that lined the imperial frontier created pathways for genetic exchange that linked this remote peninsula to the broader Mediterranean world.

One of the most compelling threads revolves around a man buried at Empúries in Catalonia, a classical Greek colony on the Spanish coast. This individual, known as I8216, carried a Y‑lineage belonging to the broader J‑PF7263 group. Earlier studies had assumed he was simply Aegean in origin, but reexamination with different reference populations reveals he carried roughly 20–30% North African ancestry, fitting best with people from Punic Carthaginian communities who were active around Empúries and along the Spanish coast.

This same Y‑branch, J‑PF7263, connects the Empúries sailor of likely Punic background to present‑day Deep Mani and beyond. A specific Maniot sub‑branch forms a close clade with a present‑day Sicilian man, with a shared ancestor around the late Roman period. Another closely related offshoot appears among Ashkenazi Jews. This whole set of related lines probably stems from the Bronze and Iron Age Levant and the wider eastern Mediterranean trading world, whose ships ranged from the Levantine coast and North Africa to Iberia.

The Punic world, descended from Phoenician settlers, had become a genetic mosaic mixing Levantine, North African, and western Mediterranean ancestries. Through this single man from Empúries, we glimpse the same east‑to‑west traffic that underpins many Maniot and Balkan lineages, revealing the interconnected nature of ancient Mediterranean populations despite the vast distances involved.

Two particularly revealing Maniot lineages tie firmly to the Bronze and Iron Age northwestern Balkans. One Maniot Y‑line, a branch of E‑V13, is identical to that of a man buried in Roman Trogir on the Croatian coast. E‑V13 appears prominently in Early Iron Age Bulgarian burial grounds. The Maniot sub‑branch has not appeared in modern Albanian samples despite intensive testing, suggesting it entered Mani before the well‑documented medieval migrations of Albanians and Aromanians. This line was more likely carried southward in Hellenistic or Roman times, perhaps by soldiers or officials drawn from the northwestern Balkans into the Peloponnese.

Another Maniot haplogroup, J‑L283, specifically its Z600 > Z631 branch, represents the overwhelmingly dominant male line in Bronze Age western Balkans, accounting for more than 70% of discovered Y‑chromosomes. Two Deep Maniots sit on this branch yet do not share close ties with present‑day Albanians, Aromanians, or other groups where J‑Z631 is present. This pattern suggests their ancestors came south in the distant past, perhaps when the Greek mainland first forged maritime and overland links with the northwestern Balkans.

The archaeological record supports this reading: related J‑L283 lines have been excavated in Bronze Age Greek sites, showing that men from the rugged western Balkans were already part of the wider Aegean story by the second millennium BCE. In Mani, these ancient movements left a small but persistent paternal fingerprint that connects this remote peninsula to the warrior cultures of the Bronze Age Balkans.

One Deep Maniot sample carries a distinctly different Y‑chromosome: a branch of R1a‑Z93. This group associates classically with the Middle Bronze Age Sintashta and Srubnaya cultures on the Pontic–Caspian steppe, whose descendants gave rise to various Indo‑Iranian nomadic peoples such as the Sarmatians. The modern Maniot carrier of this lineage matches most closely, in terms of short tandem repeat profiles, to men from the Dodecanese islands – one from Karpathos around the mid‑17th century CE and others from Rhodes.

This steppe‑derived line reached Mani comparatively late, most likely via population movements in the southeastern Aegean in the early modern period, rather than through some ancient Iron Age cavalryman. This pattern illustrates how even the most remote communities continued to receive genetic input from distant sources through maritime connections and island‑hopping migrations that characterized the later Byzantine and Ottoman periods.

The core paternal lineages J‑L930 and J‑FTF87157 function as a kind of historical map, tracing medieval population movements across Deep Mani's harsh stone landscapes. The earliest offshoots of J‑L930 cluster almost entirely in the western half of the peninsula, in villages such as Oetylo, Xoumero, Niklianiko, and Katopangi. In Katopangi, the oldest known branch of J‑L930, dated to around 850 CE, is embedded in a landscape thick with stone towers, hilltop chapels, and megalithic remains.

The earliest phases of church building in Mani concentrate in this western region, matching the places where the oldest branches of J‑L930 are found. This suggests that the families who built and used these churches represent the same male lines still present in western Deep Mani today. A mountain pass linking western and eastern Mani appears in the genetic record through lineages found on both sides, suggesting this corridor served not just as a track for pack animals and pilgrims, but as a highway for genes.

In contrast to the old, deep‑rooted western branches, eastern Deep Mani looks genetically younger. A specific branch of J‑L930 found almost exclusively in the east begins diversifying only from the early 14th century onward. This timing matches a wave of settlement visible in the archaeological record: new churches, new towers, and reoccupation of areas with older but broken traditions of habitation. The current male lines in the east seem to descend from men who arrived between roughly 1200 and 1300 CE, suggesting parts of eastern Deep Mani were largely abandoned and then resettled by people from western villages and high mountain hamlets.

The famous patrilineal clan system of Deep Mani reveals fascinating discrepancies between family traditions and Y‑chromosome evidence. The Nikliani, the celebrity clan of Deep Mani, represents not a simple story of single patriarch with neat male line, but a layered construction. Multiple sub‑branches of J‑L930 encompass different Nikliani subclans, with the main founding branches dating to the 12th–13th centuries. Some groups that no longer style themselves Nikliani still carry related Y‑lineages and retain muted memories of former kinship and dominance.

The Kosmades clan illustrates how identical names can mask different ancestries. The Taenarian Kosmades of Vatheia share Y‑lineage branching around 1422 CE, confirming their tradition of descent from two brothers. However, the Kosmades of Katopangi carry a completely different Y‑line aligned with the Nikliani, suggesting their shared name arose from political alliance rather than blood kinship. This pattern of syndrofia, or sworn companionship, created clan identities that transcended biological relationships.

The Kondostavli offer perhaps the neatest case where archive and chromosome align. First documented in 1514, all male Kondostavli share a single Y‑line within the Mani‑specific J‑L930 cluster, with a common ancestor dated around 1479 CE. Their traditional stories of settlement movements between villages match precisely with genetic branching dates, providing remarkable confirmation of oral historical accuracy in some cases.

Many Maniot clans frame their histories as sagas of noble or foreign origins – Byzantine emperors, Cretan generals, Anatolian soldiers, Sicilian traders, even Arab slaves or Ottoman janissaries. However, systematic comparison of these claims with Y‑chromosome evidence reveals that prestige often travels more readily in story than in DNA. In case after case, stories of high‑born or foreign origin appear better understood as claims to status in competitive local society rather than accurate genealogical records.

The study integrates genetic findings with Mani's remarkable archaeological landscape of cliff‑edge chapels, stone farmsteads, and scattered megaliths. Megalithic constructions, associated with Late Antiquity and early medieval land use, appear widespread in both western and eastern Mani. However, in the east, many early structures lack direct connection to the male lines dominating present‑day villages, hinting at significant breaks in continuity.

Western Mani, with its older churches and long‑rooted J‑L930 branches, appears as a relatively stable heartland. Eastern Mani, scattered with older megalithic remains but dominated by younger genetic branches, resembles a zone of abandonment and later repopulation, especially between 1200 and 1400 CE. This pattern suggests a dynamic medieval landscape where population centers shifted and communities were repeatedly founded, abandoned, and reestablished.

The distribution of early Byzantine churches correlates remarkably with the locations of the oldest genetic branches, while later phases of building correspond to newer lineage diversification. Tower clusters and farmsteads often mark the territories of specific clan branches, creating a landscape where genetic trees become visible in stone geography.

Beyond local settlement patterns, Maniot lineages connect to a broader Mediterranean story spanning millennia. Several branches relate closely to Roman‑era individuals from Croatian frontier communities, western Anatolian Byzantine burials, and Punic‑associated people from Spain and North Africa. These connections illustrate how the ancient Mediterranean functioned as an interconnected world where genetic lineages could spread across vast distances through military service, trade networks, and imperial administration.

Comments