Late Byzantine Burials and Sacred Memory at St Isidore’s Basilica, Chios

Byzantine Monumental Architecture and the Deep Stratigraphy of St Isidore, Chios

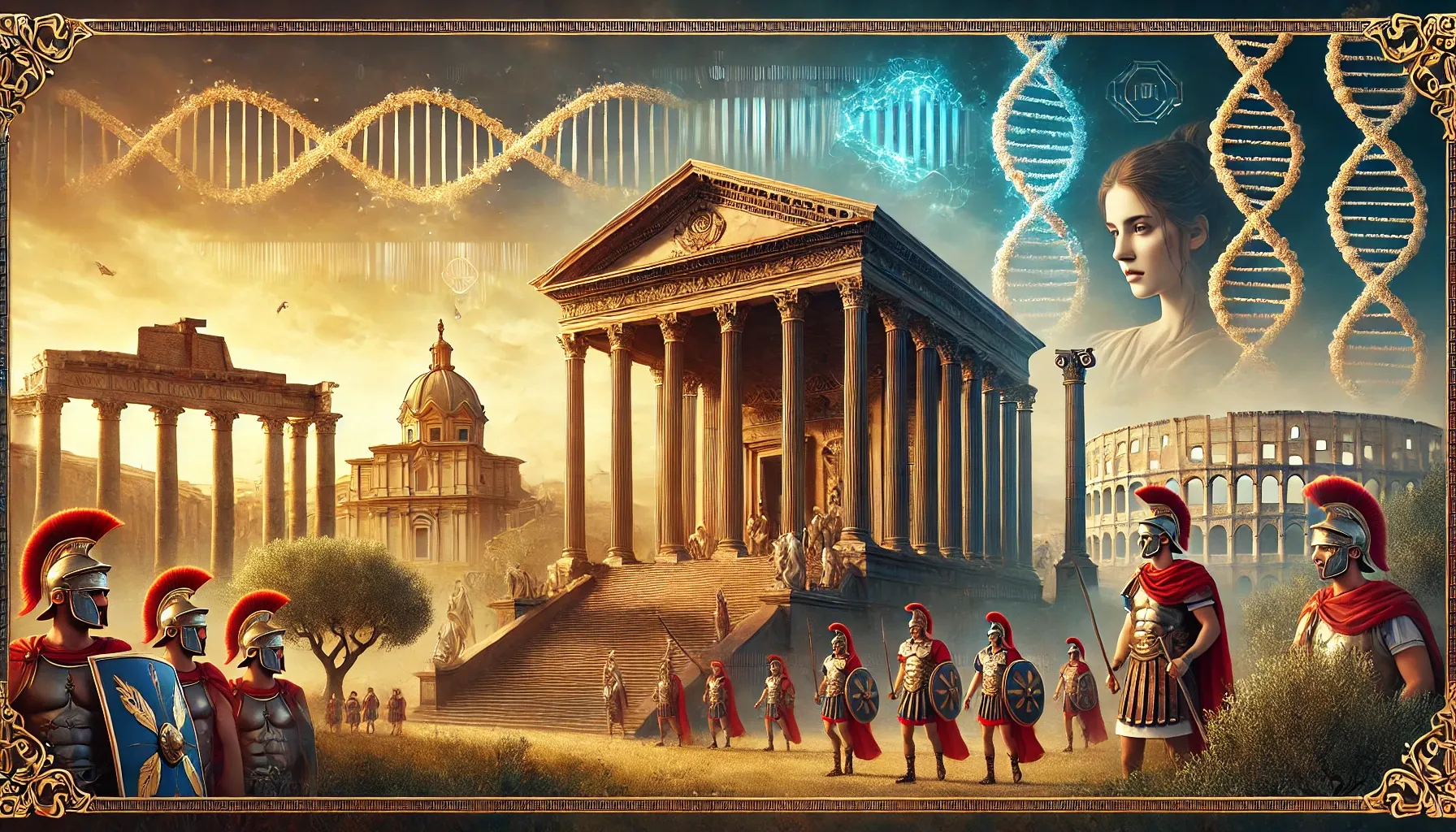

The sacred landscape of the eastern Aegean reveals one of its most compelling stories through the Basilica of St Isidore at Chios, where layers of stone, mosaic, and ruin preserve a millennium and a half of Christian architecture. This remarkable monument, wrapped around the memory of a third-century martyr and his companion Merope, offers an unprecedented glimpse into the continuity and transformation of Byzantine sacred space.

The monument stands as a building quite literally anchored in the past. The early Christian church rose over a Roman necropolis near the Chian shoreline, on a site that had already witnessed centuries of burial. Later Christians did not shun this pagan graveyard but appropriated it, building their basilica on top. Even the great blocks and stylobates that supported the Christian columns began life in Classical architecture, hauled, cut down, and reused as foundations. The site thus emerges as a palimpsest where Roman tombs and Classical stonework were overlaid by a grand Christian complex.

The basilica did not remain static through the centuries. Earthquakes, Arab raids, pirate attacks, fires, and war repeatedly shattered it. Each disaster prompted rebuilding, repair, or partial abandonment. Archaeological investigations by early twentieth-century excavators Sotiriou and Orlandos, and later the 1980s campaign of Pennas, mapped out the tangled sequence of at least five main building phases, each church nudged slightly southwards or reworked inside the ruined shell of its predecessor.

Archaeologists traced an original three-aisled basilica with a horseshoe-shaped apse, probably created in the later fifth century by adapting an earlier structure. Its floors were clothed in shimmering mosaic panels, some of which were themselves re-used from an even earlier church. A later seventh-century phase, associated in tradition with Emperor Constantine IV Pogonatos, rebuilt the monument after an Arab attack, again adorning its interior with mosaics and columns made expressly for this grand basilica.

By the middle of the sixth century and beyond, enlargement became the rule. One basilica after another was laid out just to the south of the previous one, cannibalising earlier walls as stylobates for new arcades. Pagan architectural fragments were once more pressed into service as the hidden bones of a Christian monument. Still later, probably in the Middle Byzantine period, a more compact cross-in-square church was inserted inside the footprint of the great basilica, using spolia on foundations that showed signs of hasty construction.

Historical sources speak of a great dome cracked by an earthquake in the late fourteenth century and then finally destroyed in the catastrophic quake of 1881. By the time the historian Zolotas visited in 1866, he found a burned, stripped, half-ruined church, its floor buried under sediment and vegetation. Twenty years later, even that wreckage had collapsed into amorphous piles of stone, marking the end of more than a millennium of continuous sacred use.

Against this background of shifting architecture, one feature stands out with particular significance: a grave cut straight through the lavish mosaic floor of the nave. During rescue excavations in 1982, beneath a thin modern concrete patch aligned with the surviving mosaic fragments of the raised western nave, archaeologists uncovered an intrusive burial pit measuring approximately 2.15 by 1.70 metres.

The grave sliced into the mosaic associated with the third major basilica phase. Yet when later builders raised the cross-in-square church of the fourth phase inside the old basilica shell, this very mosaic panel, complete with the intrusive burial, still formed part of the church floor, positioned just inside its western entrance. The grave thus occupied an exceptionally prominent location, under the feet of worshippers as they stepped in from the narthex, at the threshold between outside world and sacred space.

Within this carefully placed grave, the excavators found the commingled remains of two individuals, designated Homo I and Homo II in the archaeological record. Their bones, photographed in situ and then analysed in detail, reveal complementary stories that illuminate both Christian burial practices and the social fabric of medieval Chios.

Homo I was the primary burial, his skeleton lying in anatomical order, supine, stretched out on his back with head to the west and face turned toward the east. This represents the classic arrangement for Christian inhumation, pointing the body toward the liturgical east and the rising sun. His head was gently propped on a neatly cut cuboid stone pillow, suggesting deliberate care in his final presentation.

No coffin fittings or wood traces were found, but the position of arms and hands, with forearms flexed and hands folded over the abdomen, creates a dignified, composed effect. Osteological analysis reveals a man of modest build, about 1.66 metres tall, with teeth that speak of a carbohydrate-rich diet and middle-aged wear. He died around 38 to 48 years of age, in what the researchers classify as late adulthood shading into mature years.

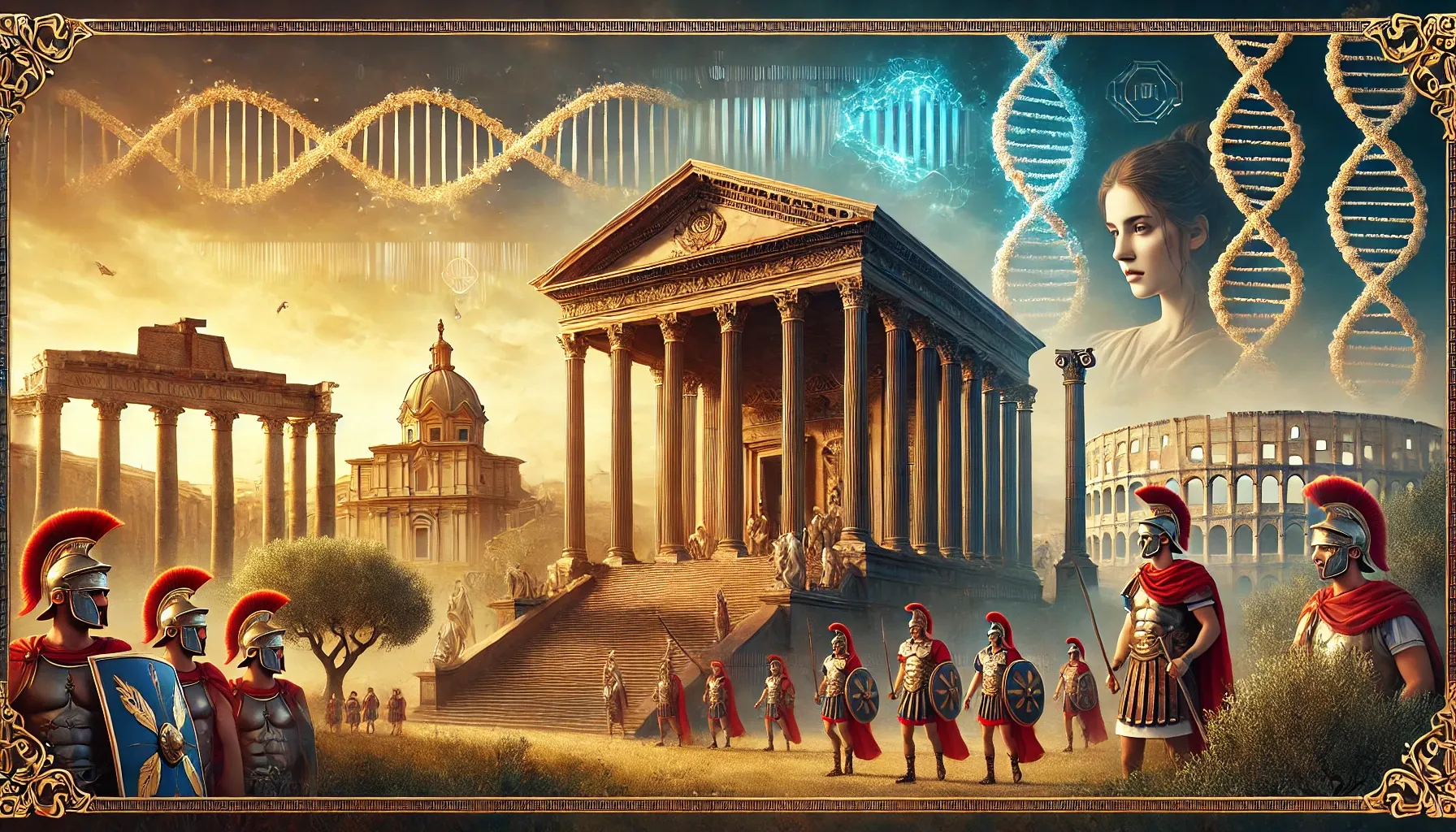

Later genetic work confirms that he was biologically male. His DNA places him firmly among the local population of the eastern Aegean, genetically close to present-day Dodecanese islanders and late Roman-Byzantine communities in western Asia Minor. One particularly intriguing aspect of his genetic profile emerges from his Y-chromosome, which carries a branch of lineage R-Z93, predominantly Asian in distribution and closely linked to historical Indo-Iranian speaking populations. This suggests that a distant male ancestor may have belonged to an Iranic-speaking group that became integrated into the local Greek population over many centuries.

Homo II presents a markedly different picture. Her remains were found in a shallow scooped depression at the eastern end of the grave, just beyond the feet of Homo I. The bones were badly fragmented, disarticulated, and pushed together, indicating that she had not been laid out afresh as a whole body but had been disturbed from an earlier burial and re-placed in a classic case of secondary burial.

This practice reflects familiar Christian custom: when opening a family or privileged grave to insert a new burial, earlier remains might be reverently rearranged within the same pit to make room. Homo II is thus earlier in date than Homo I but housed in the same architectural location, suggesting a deliberate decision to maintain the sanctity of the burial spot while accommodating a new interment.

Although her bones are incomplete, the muscle markings on surviving elements show a robust, strongly built person. Dental and pelvic changes point to an age at death between approximately 55 and 65 years. Initial attempts in the 1980s to sex the skeleton based on morphological appearance alone hesitated between identifying it as a powerful older woman or a smaller-framed man. Ancient DNA has now definitively settled the matter, confirming that Homo II was biologically female.

Genetically, she belongs to the same local population as Homo I, with no indication of foreign origin or hint of outsider status. The two individuals are not close kin, neither mother and son nor siblings nor cousins, but rather two unrelated Chians sharing the same grave, brought together by circumstances other than blood relationship.

Radiocarbon dating of both individuals places their lives and deaths squarely in the turbulent late thirteenth century. For the woman, calibrated dates cluster strongly between 1257 and 1300, while for the man, the highest probabilities range from 1274 to 1303. These remarkably tight chronological constraints allow for detailed historical contextualisation.

Working backward from death dates and estimated ages at death, the woman's life span can be reconstructed as approximately 1197 to 1279, placing her birth in the troubled years before the Fourth Crusade and her death during the period of Nicaean rule and Byzantine recovery. The man's lifespan falls roughly between 1231 and 1289, meaning he was born during the Latin occupation and died in the generation following the restoration of Byzantine control.

These dates are particularly significant because they long predate the documented 1389 earthquake that damaged the dome of the later church. The burials fall into what appears to have been a transitional period when the earlier basilica had fallen out of regular liturgical use but before the cross-in-square church of the fourth phase was constructed. The grave, dug through the nave mosaic, thus marks significant commemorative activity in a building that may no longer have been functioning as a full parish church but retained its sacred character and prestige.

One of the most compelling aspects of this discovery is how it illuminates ordinary lives against the violent backdrop of thirteenth-century Aegean history. The calibrated dates for both individuals overlap with a period of repeated raids and devastations of Chios. Chronicles speak of Roger de Luria and later Roger de Flor bringing Almogavar mercenaries to plunder the island. Turkish fleets attacked with dozens of ships, stealing goods and seizing women and children as slaves.

The man and woman buried under the St Isidore nave cannot be tied to any particular raid or political event, but they almost certainly lived through or died in the wake of these traumatic experiences. Their bones, local and unremarkable in genetic terms, become emblematic of the ordinary islanders whose lives unfolded in the shadow of larger political catastrophes. They represent the human cost and continuity of a community that endured conquest, liberation, and repeated assault while maintaining its cultural and religious identity.

The placement of the grave demonstrates careful planning rather than casual intrusion. The pit exploits the step between the raised western nave floor and the lower central mosaic, taking advantage of the height difference to dig a substantial trench without undermining surrounding structures. Its northern long side abuts the old stylobate that once separated nave from north aisle in the earliest basilica, a line that later became the base for the iconostasis of the cross-in-square church.

When the fourth-phase church was eventually erected, this grave lay just inside the western entrance, on axis with the holy door into the sanctuary. Worshippers would have stepped across splendid Chian stone mosaics, perhaps unaware that beneath their feet, under a section that showed signs of repair, lay the bones of two honored members of their community from the island's most troubled century.

The grave also sits within the conceptual heart of the cult of St Isidore. Hagiographic tradition insisted that Constantine Pogonatos himself had constructed a magnificent church over the martyrs Isidore and Merope, whose burial place lay somewhere within this sacred complex. For centuries, pilgrims, monks, and learned antiquarians believed that the floors of St Isidore's basilica quite literally sealed the resting-place of the saints, making any burial within the nave a participation in that holy presence.

Comments