Exploring Viking Age Genetics: Insights from Population Genomics and Ancient DNA

The Viking Age, stretching from circa 800 to 1050 CE, represents a captivating period rich with the endeavors of Scandinavian seafarers. These Norse explorers were not just isolated marauders but crucial participants in cultural and economic exchanges that spanned continents. Recent archaeological discoveries combined with genomic research have dramatically enhanced our understanding of this dynamic era, revealing a complex picture of exploration, trade, conflict, and settlement.

The Vikings established extensive networks that reached across the North Atlantic, the British Isles, the Baltic region, and at times extended to the Mediterranean and the East. As they voyaged, they adopted and influenced the Christian religion and monetary systems they encountered, creating a legacy that shaped European history for centuries to come.

Explore your own link to Vikings: visit MyTrueAncestry and upload your DNA to begin.

The groundwork for the Viking Age was laid well before the 8th century. Evidence shows that as early as the late Roman Period (200-375 CE), Scandinavian societies actively engaged with the Roman Empire. Archaeological findings document large-scale migrations into Western Europe, specifically marked by the Anglo-Saxon settlement in England by groups from what are now Northern Germany and Denmark.

A critical turning point occurred between 530–550 CE with the 'Late Antique Little Ice Age,' a global climatic downturn precipitated by volcanic activity. This period was marked by crisis - famine and the infamous Justinian Plague ravaged populations across Europe. These twin calamities potentially wrought demographic changes across Scandinavia, inviting new genetic influences as populations fluctuated and reformed.

The 7th and 8th centuries witnessed transformations in material culture that heralded what historians term the 'Viking phenomenon.' This era coincided with advancements in seafaring technology—particularly the development of the keel and sail—that propelled Nordic explorers across vast distances. Trading hubs like Birka in Sweden and Staraja Ladoga in Russia began as humble settlements before flourishing as focal points of exchange, connecting Scandinavia to a broader world.

One of the most remarkable discoveries came from Salme, Estonia, where two Early Viking Age ship burials were uncovered in 2008 and 2010. Dating to approximately 750 CE, these burial ships contained the remains of over 40 warriors, arranged in layers and accompanied by:

DNA analysis revealed fascinating details about these warriors, including evidence that four of them were brothers, suggesting familial bands that fought and died together. The genetic evidence connects these individuals to regions in Scandinavia, illustrating the reach of Viking expeditions even in this early period.

The cemetery at Kopparsvik on the island of Gotland, Sweden, has yielded graves dating from 900 to 1050 CE. These burials are notable for artifacts that demonstrate the islanders' expansive trade connections:

Isotopic analyses indicate diets rich in terrestrial food rather than marine sources, while DNA results show genetic blending that reflects Gotland's position as a hub of international exchange.

Norse settlements in Greenland, such as Sandnes, provide insight into Viking colonization efforts in the North Atlantic. These sites feature:

Skeletal analyses and DNA studies suggest these settlers maintained their Norse identity and customs despite their remote location. Intriguingly, their genetic makeup shows no evidence of admixture with Inuit or Native American populations, despite their geographical proximity.

In the Faroe Islands, medieval graves at Sandur reveal a story of selective burial practices sustained by familial bonds. These islands present a unique genetic profile that maintained connections with Scandinavia while developing in relative isolation. The burial sites indicate elite status, suggesting these remote settlements were established by prominent Viking families.

Archaeological sites in the Orkney Islands and along the Scottish coast reveal complex cultural interactions. DNA evidence suggests that some individuals traditionally identified as Vikings may have been locals who adopted Norse lifestyles and customs. This genetic evidence illuminates how incoming Norse settlers blended with local Pictish populations, creating hybrid cultural identities.

Viking burial practices show significant variation across different regions of Scandinavia and changed over time:

This diversity of burial methods has provided researchers with various contexts for DNA sampling and analysis.

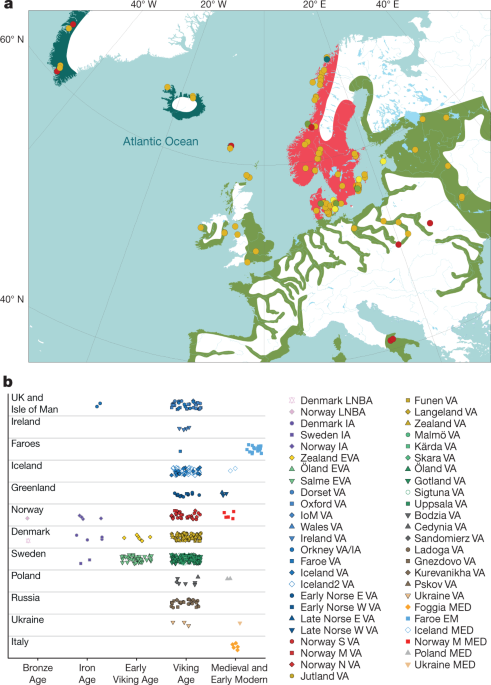

During the Viking Age (ca. AD 750–1050), Scandinavians expanded widely by sea, influencing the genetics of many regions. Researchers sequenced the genomes of 442 ancient individuals to study this impact. Particularly valuable sources included:

These samples ranged from the Bronze Age through to the early modern period, providing a chronological framework for understanding genetic changes over time.

One of the most compelling aspects of genomic research is the ability to identify family relationships among ancient individuals:

These genetic connections humanize the Viking Age, allowing us to see beyond the broad strokes of history to the intimate relationships that bound individuals together.

DNA analysis has revealed surprising patterns of movement and migration:

These patterns confirm some historical accounts while challenging others, providing a more nuanced understanding of Viking expansion.

Perhaps most surprisingly, the genomic evidence reveals the Vikings as genetically diverse people who readily integrated with local populations:

This genetic evidence contradicts the popular image of Vikings as a homogeneous group and instead portrays them as cosmopolitan people engaged in constant cultural and genetic exchange.

The combination of archaeological discoveries and genomic research has transformed our understanding of the Viking Age. Far from being a simple narrative of raiding and pillaging, this era emerges as a complex period of human interaction, cultural exchange, and adaptation.

The DNA extracted from Viking burial sites tells a story of a people who were simultaneously fierce warriors, skilled traders, ambitious colonizers, and adaptable settlers. Their genetic legacy reveals both their distinctive Scandinavian origins and their willingness to integrate with the diverse populations they encountered in their travels.

As research continues, the picture of Viking society becomes increasingly nuanced, allowing us to see these ancient seafarers not as one-dimensional characters from legend, but as real human beings whose lives, families, and journeys have left an indelible mark on European history and genetics.

Comments