Bell Beaker–Driven Population Turnover in the Rhine–Meuse Region

Hunter-Gatherer Continuity and Mixed Lifeways in the Rhine–Meuse Wetlands

The Rhine–Meuse region presents one of European prehistory's most fascinating stories of cultural and genetic continuity. This waterlogged landscape of rivers, peat bogs, and shifting dunes spanning modern Netherlands, Belgium, and western Germany harbored populations that stubbornly refused to fit the standard European Neolithic narrative. While much of Europe shifted rapidly to full-time farming with heavily diluted hunter-gatherer ancestry, Rhine–Meuse communities maintained mixed lifeways and distinctive genetic identities for millennia.

Advances in archaeogenetics have made it possible to trace our DNA back thousands of years, linking us to cultures long lost to time. You can see where your lineage fits in this vast human map at MyTrueAncestry.com.

North of the fertile loess belt where early farmers established themselves, the great rivers Scheldt, Meuse, and Rhine created a complex delta ecosystem. From approximately 5000–3500 BCE, Swifterbant and Hazendonk communities settled on modest elevations: river dunes, coastal ridges, levees, and crevasse splays rising above the marshlands.

Archaeological evidence reveals these populations practicing neither pure foraging nor classic farming, but rather maintaining sophisticated mixed economies. They hunted, fished, and gathered while simultaneously keeping domestic animals and cultivating crops. Ancient DNA analysis confirms this intermediate lifestyle: early Swifterbant individuals carried remarkably high hunter-gatherer ancestry, often around fifty percent or more, during periods when most European farming communities had dropped to well below thirty percent.

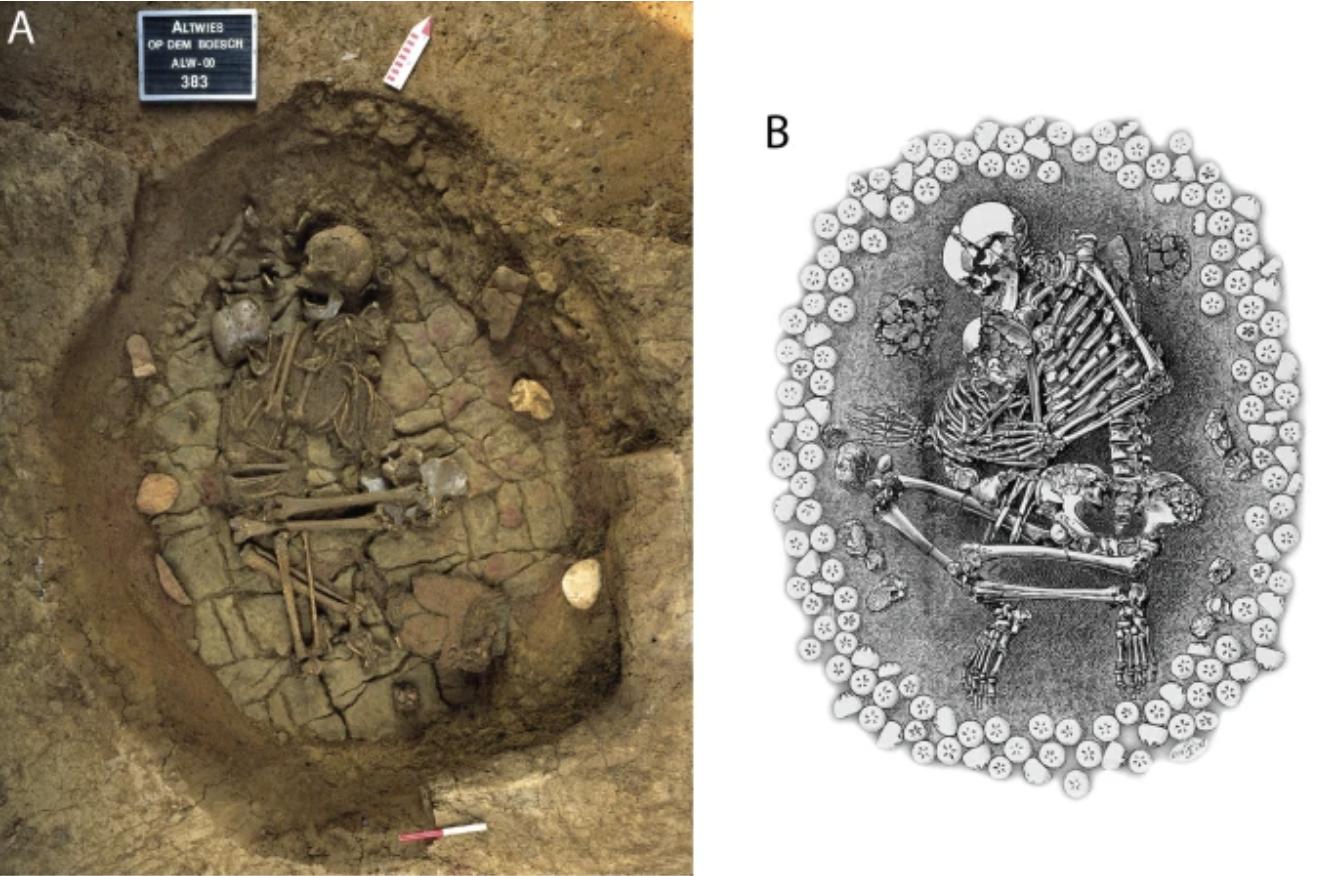

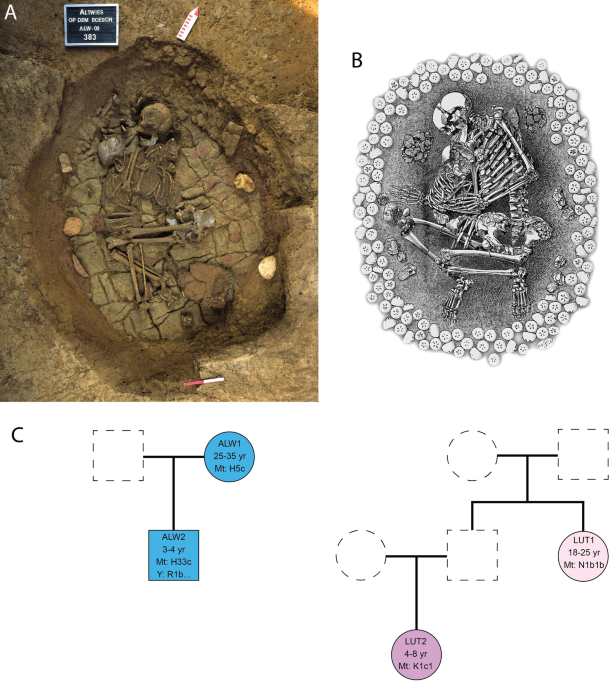

Several pivotal sites illuminate this mixed world. At Swifterbant S2 and Nieuwegein, settlements perched on river dunes reveal communities blending traditional fishing and hunting with early agricultural practices. Particularly striking are burials including a mother-daughter pair from Nieuwegein (individuals I12093 and I12094) who lived in settlements experimenting with domesticated animals and crops yet remained genetically connected to Mesolithic hunter-gatherer populations.

The site of Hardinxveld-Giessendam provides exceptional preservation of organic materials, revealing sophisticated fishing equipment, wooden tools, and evidence of seasonal mobility patterns. At Zoelen-De Beldert and Tiel-Medel, archaeological layers demonstrate gradual adoption of farming techniques alongside persistent reliance on wild resources.

This pattern extends eastward along river systems. Middle Neolithic populations from Blätterhöhle cave and Wartberg culture sites in northwest Germany, plus various Neolithic groups in Belgium, maintained unusually high hunter-gatherer ancestry for such late dates. Genetic data and river system distributions tell consistent stories: interconnected communities stretched along waterways, sharing preferences for woodland hunting and fishing while experimenting with agricultural innovations.

One of the most remarkable findings concerns population movement and marriage patterns. Rhine–Meuse Neolithic genetics show that early farmer genetic contributions were strongest in genome portions more influenced by women and in maternal lineages. Y-chromosomes, transmitted father to son, remained almost exclusively of types characteristic of Mesolithic hunter-gatherers.

This pattern suggests local hunter-gatherer-descended men consistently married women from farming backgrounds. These women served as primary carriers of agricultural knowledge into wetland communities, functioning as vectors of ideas alongside genetic contributions. They brought seeds, livestock, pottery technologies, and organizational systems while joining societies still heavily dependent on riverine wild resources.

Simultaneously, extensive identical DNA stretches shared between individuals buried across vast distances demonstrate this water-linked world's connectivity. Genetic relationships link people from Blätterhöhle in western Germany to Mont-Aimé in northern France to Ardennes caves, suggesting cousin relationships and extended family networks scattered across hundreds of kilometers, following river and coastal routes rather than overland paths.

Around 3500 BCE, the Vlaardingen culture emerged in western Netherlands, succeeding Swifterbant and Hazendonk while maintaining similar territorial preferences for water and marsh zones. Vlaardingen sites at Hellevoetsluis, Medel, and related locations show intensified farming tool usage and ard plough introduction by approximately 3000 BCE. However, this represents intensification rather than revolutionary change: hunting, fishing, and gathering persisted alongside expanding agricultural activities.

Simultaneously, Funnel Beaker (TRB) farmers settled dry sandy uplands of the Friesian–Drenthian plateau, apparently occupying previously unoccupied areas. Southward, Michelsberg farmers cultivated loess soils. These surrounding farming communities followed distinct settlement patterns, pottery traditions, and monument construction practices.

What emerged was an anthropological frontier: not a rigid boundary but a zone where different lifeways coexisted and interacted. For centuries, riverine peoples and upland farmers remained genetically and culturally distinct while exchanging ideas and individuals, particularly women from farming groups. Rather than wholesale replacement, wetlands supported resilient semi-agrarian adaptations lasting far longer than elsewhere in western and central Europe.

Throughout Europe, Corded Ware material culture appearance around 2900–2500 BCE typically accompanied large-scale migrations of people carrying steppe ancestry from eastern regions. The Rhine–Meuse wetlands tell a markedly different story.

On sandy uplands, classic Corded Ware burial mounds appeared, though bone preservation prevented DNA analysis. In lowlands, Corded Ware pottery appeared in everyday Vlaardingen tradition settlement contexts, while characteristic graves remained largely absent. Where burials permitted DNA analysis, individuals buried with Corded Ware-style objects resembled long-standing local populations.

At Molenaarsgraaf, a woman (I12896) buried in Vlaardingen/Corded Ware context showed no detectable steppe ancestry, genetically belonging to the traditional Rhine–Meuse hunter-farmer world. At Mienakker and Sijbekarspel–Op de Veken, individuals showed only approximately eleven percent steppe-related ancestry, with remainder matching local Neolithic genomes rich in hunter-gatherer heritage.

However, the Mienakker man (I12902) carried Y-chromosome type R1b-U106 known from early Corded Ware burials in Bohemia. Despite predominantly local autosomal ancestry, his paternal lineage clearly connected to steppe-derived populations. This suggests relatively small numbers of incoming men, or perhaps single notable lineages, married into existing wetland communities. Corded Ware pottery and associated ideas arrived without sweeping demographic change characteristic of other regions.

Around 2500 BCE, fundamental changes finally occurred. Bell Beaker phenomenon arrival in Rhine–Meuse delta correlated with substantial population influx. Famous Bell Beaker graves, characterized by distinctive beakers, archery equipment, and ornaments, spread across wetlands and sandy uplands, replacing earlier settlements while often selecting new locations.

Thirteen Bell Beaker-associated individuals from the region clustered genetically with central European Corded Ware groups rather than older Swifterbant–Vlaardingen lineages. They carried approximately eighty-three percent ancestry from Corded Ware-like sources. However, remaining nine to seventeen percent necessarily derived from local Rhine–Meuse farmers with characteristic high hunter-gatherer components. Statistical models excluding this local contribution failed to fit genetic data.

Y-chromosome analysis revealed remarkable uniformity among Bell Beaker men. All well-preserved samples belonged to R1b-L151 lineage, predominantly the P312 sub-branch dominating Bell Beaker burials throughout Europe. One Early Bronze Age individual carried U106 type, matching the earlier Mienakker Vlaardingen/Corded Ware context. The same steppe-derived lineage families apparently presided over both limited Corded Ware impact and later, more dramatic Bell Beaker influx.

Identity-by-descent analysis demonstrated that from the Bell Beaker period forward, the Rhine–Meuse region integrated into much wider kinship networks. Individuals buried in Dutch wetlands shared substantial DNA segments with people extending to Bohemia in central Europe and Early Bronze Age individuals in Britain. Rivers and coasts that once sustained distinctive wetland frontiers now functioned as highways for far-reaching mobility.

The article traces Bell Beaker group impact as they expanded into Britain. Genetic modeling demonstrates that most Bell Beaker-associated British individuals can be explained as mixtures of Corded Ware-derived ancestry and distinctive Rhine–Meuse Neolithic ancestry with characteristic high hunter-gatherer components. Little or no ancestry from Britain's earlier Neolithic farmers appears necessary.

Famous figures like the Amesbury Archer, buried near Stonehenge with spectacular grave goods including gold ornaments, copper knives, and stone wrist-guards, represent slight genetic outliers with lower steppe ancestry and isotopic signatures suggesting Alpine childhood. However, main Bell Beaker populations in Britain appear overwhelmingly descended from groups whose formation centered in Rhine–Meuse regions.

Bell Beaker expansion into Britain implied not merely traders and warriors crossing the North Sea, but entire families reshaping the island's gene pool. Yet these newcomers also adopted local traditions: continuing round house construction, utilizing traditional stone sources, and maintaining monument complexes like Stonehenge while introducing new burial styles and material culture.

Discover how your DNA connects to ancient civilizations at www.mytrueancestry.com.

Comments