Ancient Sacrifice in Neolithic Shimao, Northern China

The Genetic History of Shimao: Ancient DNA Reveals Continuity and Contact on China's Northern Frontier

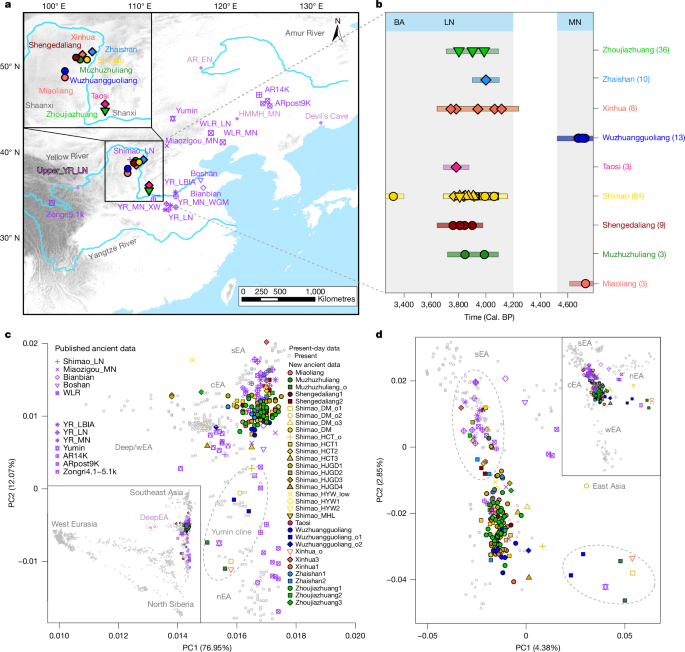

The genetic story of Shimao traces back more than a thousand years before the great stone city rose on the northern Loess Plateau. Through analysis of DNA from 144 ancient individuals, research reveals that Shimao's builders were not mysterious newcomers from distant lands, but largely the descendants of earlier farming communities associated with the Yangshao culture in northern Shaanxi. This continuity challenges assumptions about sudden population replacement and instead reveals how established communities transformed themselves into complex urban societies.

Long before Shimao's massive stone walls and sacrificial gates, the same region was dotted with smaller Yangshao-era settlements. Two such sites, Miaoliang and Wuzhuangguoliang, have provided human remains from around 4,800 years ago, representing a "pre-Shimao" population that inhabited these dusty highlands. These earlier communities belonged to the painted-pottery farming world of the Yangshao culture, and genetically, they already carried the basic ancestry that would dominate the region for the next millennium.

When DNA from people at Wuzhuangguoliang is compared with later Shimao-period individuals, they cluster strikingly close together. Statistical modeling demonstrates that Shimao's population can be treated as drawn entirely from this earlier Yangshao-related group, without requiring any additional mysterious ancestral source. Simply put: the farmers were already there, and their descendants went on to build the city.

The rise and fall of ancient peoples left marks not only on the landscape but also in our genes. If you’ve ever wondered how your ancestry fits into that larger historical mosaic, MyTrueAncestry.com offers a fascinating perspective.

Around 4,200–3,800 years ago, Shimao emerged as a vast fortified city with thick stone walls, carefully planned enclosures, and unmistakable hierarchy in its cemeteries and sacrificial areas. Genetically, however, the people buried in and around the city were not a new population. They carried essentially the same Yangshao-derived ancestry seen at Wuzhuangguoliang centuries earlier. This cluster of Late Neolithic people included not only Shimao itself but several satellite sites: Muzhuzhuliang, Shengedaliang, Xinhua and Zhaishan.

These settlements formed an interconnected network of communities sharing deep ancestry while participating in the new, highly stratified Shimao culture. At Zhaishan, a cemetery with clearly ranked graves shows extended families maintaining status across generations. Male tomb owners often share the same paternal line, while their overall ancestry still links back to the older Yangshao-related population. This suggests local continuities rather than foreign domination.

The most striking pattern is how little the genetic story changes as the archaeological record becomes more dramatic. Between the modest Yangshao-era villages and the stone-walled metropolis with its palatial Huangchengtai platform and blood-soaked East Gate, the core ancestry remains remarkably stable. In an era when new technologies, luxury goods and perhaps new ideologies were circulating widely, the people of Shimao appear to be long-term inhabitants of the Loess Plateau organizing themselves into a far more complex and unequal society.

Within Shimao city itself, two cemeteries are particularly revealing: Huangchengtai at the center, and Hanjiagedan just to the south. These high-status burial grounds contained rich grave goods, stone coffins, and in many cases human sacrifices. Yet DNA examination reveals that the tomb owners belonged squarely to the same Yangshao-derived genetic tradition as their supposed peasant ancestors. Reconstructed pedigrees across three and four generations in these cemeteries show noble lineages rooted in a single dominant paternal line, still carrying the old regional ancestry from Wuzhuangguoliang.

One noble man at Hanjiagedan, buried with sacrificed companions and elite objects, can be placed at the top of an extended family tree. His descendants, also buried with signs of status, still carry the characteristic Yangshao-derived ancestry that defines Shimao's population. Political power may have crystallized at Shimao, but DNA links these rulers back to long-resident farming communities of the plateau.

While core ancestry remains Yangshao-related, the study reveals modest additional strands woven into the genetic tapestry. A handful of "southern-leaning" individuals at Shimao and its satellites show traces of ancestry related to populations far to the south, including groups from coastal Fujian and ancient island communities off Taiwan. These outliers still derive 70–90% of their ancestry from the local Yangshao-related background, but around 10–30% comes from southern sources. This fits well with evidence for rice farming pushing northward earlier and farther than previously believed.

Another thread comes from the north and northwest. Some individuals at Wuzhuangguoliang, and later a series of striking outliers at Shimao and nearby sites like Muzhuzhuliang and Xinhua, carry ancestry closely related to the Yumin population from the Inner Mongolian steppe. These people stand apart in genetic analyses, forming a "Yumin cline" distinct from the main Shimao–Yangshao cluster. Yet even here, the story is one of addition rather than replacement. Yumin-related ancestry appears in a few individuals over many centuries, sometimes as pure steppe-like profiles, sometimes mixed with the local Yangshao background, but never overwhelming the regional genetic character.

A thousand years later, when Shimao city dominated the plateau with its stone ramparts, planned streets and sacrificial pits, Yumin-related ancestry appeared again. Six Late Neolithic individuals, dated roughly 4,100–3,400 years ago, cluster genetically with Yumin rather than with the local Shimao majority. These outliers come from several key sites, including the elite core at Huangchengtai, the East Gate sacrificial area, and satellite settlements like Xinhua and Muzhuzhuliang.

Some of these individuals appear genetically as almost entirely Yumin-derived, looking like northerners who had arrived more or less intact. Others represent true hybrids, with roughly 30% Yumin-related and 70% local Yangshao-related ancestry. What makes these people particularly fascinating is not just their ancestry, but the places where their bones were found.

The ancient DNA analysis reveals Shimao as a place where power, kinship and killing were tightly woven together. By combining archaeology with genetics, researchers reconstructed who was sacrificed, who ruled, and how sex and status shaped the brutal rituals that marked this early urban society. The results reveal striking patterns in sacrificial practices that varied by location and social context within the city.

At Shimao's East Gate, mass burials of decapitated individuals placed beneath the foundations revealed a dramatic reversal of previous assumptions. While earlier work based on skeletal shape suggested these were mostly women, genetic analysis shows that nine out of ten sampled victims were male. These men were likely part of construction rituals, their bodies literally packed under the gateway to sanctify and protect the city. This represents one of the earliest genetic glimpses of a clearly male-biased sacrificial rite in Neolithic China.

In contrast, inside the city at high-status cemeteries, sacrifice was overwhelmingly female. At Hanjiagedan, nearly all sacrificed individuals accompanying elite tomb owners were women, while at Huangchengtai, fourteen out of nineteen sacrificial individuals were female. These women were killed to accompany elites into the afterlife but showed no close biological relationships to the tomb owners, suggesting they were selected from outside the elite families.

Discover how your DNA connects to ancient civilizations at www.mytrueancestry.com.

Comments